You’ve heard it before, probably more times than you’d care to: These are “uncertain times.”

Mostly, that means we’re in an era rife with challenges, both immense and trivial. But uncertainty also comes with opportunity. There’s a really refreshing sense of freedom and possibility that’s born of collective confusion.

We’ve spent the past months chatting with smart people from around Kansas City and the region about big ideas to solve our most intractable problems and create a better future.

The topics explored in our Big Ideas feature tend toward the ambitious. Some might say a few are pipe dreams. Self-piloted air taxis powered by a local company’s technology and a local billionaire rescuing the Star from hedge fund jackals may seem outlandish until you read up on them.

Other ideas are such obvious winners that it’s surprising no one has done them already—why is there no marina on this stretch of the Missouri River?

But all of these big ideas have the ability to inspire as we finally emerge from a long, dark slog where it was sometimes harder to dream any bigger than getting dinner on the table and vacuuming the baseboards in the same evening.

The future is coming on fast. And what it looks like is—well, that’s up to us. Here are eleven spots to start the conversation.

What if Kansas City becomes the Detroit of flying cars?

If you had a Garmin GPS unit back in the brick-phone era, you probably remember it as revolutionary. Well, there’s another game-changing technology brewing in Olathe, one that could shape not only global transportation but also our regional economy.

Garmin Autoland is what it sounds like: technology that can safely land an airplane if the pilot is incapacitated. The technology debuted last year and in that short time has captured the imagination of the aviation world.

Once you’ve got a plane that can plot a clear path to an airport and safely land on its own if a pilot is incapacitated, it’s not a huge leap to—yes, Mr. Jetson, we’re going there—flying cars. Self-flying cars.

“I can’t say that we are currently working toward making this technology compatible with entirely autonomous aircraft operations,” says Conor McDougall, the media relations specialist for the company’s aviation segment. “But I will say we are always working on innovating and helping our amazing technology reach other parts of the segment, with a proven history in doing so.”

Garmin recently inked a deal with Joby Aviation, which is making all-electric vertical takeoff and landing aircraft. Joby plans to operate commercial air taxi services as early as 2024. The first iteration won’t use Autoland, but McDougall notes that “there is a lot of speculation that automation will be a key part of this market’s growth in the future.”

Being such an important piece of the future of transportation bodes well not just for a keystone KC company but for the entire regional economy. —Martin Cizmar

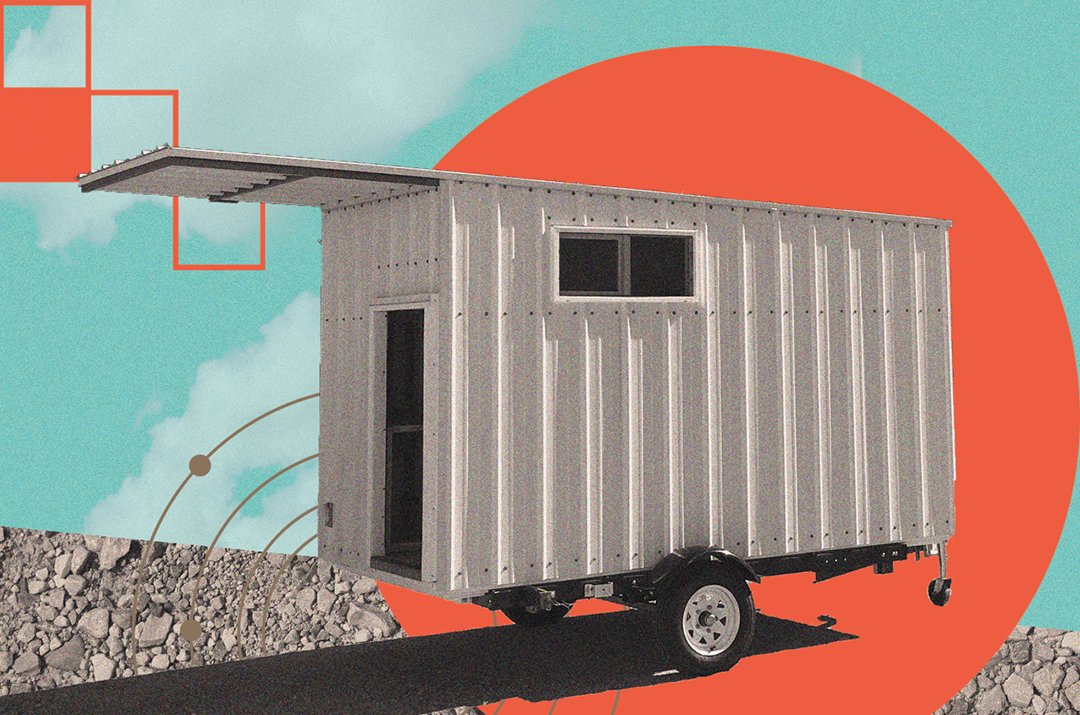

What if portable tiny homes could change the homeless shelters for the better?

Everyone seems to care about the well-being of homeless people, but very few are eager to welcome them into their neighborhood—especially not in the form of a permanent shelter.

Dan Rockhill, a KU professor of architecture, thinks he has a compromise in the form of portable tiny homes, which he and his graduate students are already putting into practice with a project called the Lawrence Community Shelter.

“Everyone is concerned with the homeless, but the city doesn’t want them in their backyard or next door,” Rockhill says. “It’s very difficult for cities to find ways to help the homeless without people getting mad at them.”

Tiny homes offer a more private setting for homeless families as opposed to overcrowded shelters. They’re also safer, especially during the pandemic.

Each of Rockhill’s homes includes a bathroom and a small kitchen that offers a comfortable, homey feel.

Each can host four people, and they are building a dozen homes in Lawrence. These unique homes are built from repurposed shipping containers with a wood-finish interior. Another feature that makes these tiny homes stand out from other shelters is that they include furniture in each unit—bunk beds, a trundle bed as well as cabinets and countertops. —Amijah Jackson

What if an eye in the sky could slow the city’s homicide epidemic?

Kansas City had a record one hundred seventy-four homicides in 2020, and we weren’t alone. Cities across the country were hit with a spasm of gun violence: Chicago’s murder rate jumped fifty percent from 2019. Los Angeles was up thirty percent. New York was up forty percent. Nationally, the best estimate is a leap of thirty-six percent.

One notable outlier? Baltimore.

Almost unbelievably, in one of the nation’s most notoriously violent cities, the murder rate actually dropped last year, despite the pandemic and cresting wave of social unrest. The city of Baltimore had three hundred thirty-five homicides in 2020, thirteen fewer than the year before, despite a surge in deadly domestic violence.

What accounts for the difference? Dr. Ross T. McNutt thinks his company, Persistent Surveillance Systems, played a role.

McNutt is an MIT-educated former Air Force officer who developed technology to use high-flying. airplanes with super-powered cameras to track the militants who were devastating American forces with IEDs in Fallujah. After a roadside bomb went off, analysts would reverse the tape, following the attackers back to their lairs.

“We would follow the dots,” McNutt says. “We’d go from the explosion backwards and forwards in time to try and find out who planted it. Which, by the way, is the exact same thing we do when we watch a murder. We follow people to and from the murder scene.”

High-flying surveillance is especially effective when combined with acoustic gunshot detection systems, which can pinpoint the time and general location that a shot is fired, and effective police access to private ground cameras.

“We caught a killer once who stopped for gas on the way to the murder, and we found him on camera handing a five-dollar bill to the clerk,” McNutt said.

From April to October 2020, Baltimore was patrolled by a Cessna prop plane (a fraction of the cost of the cheapest drone) equipped with a 192-megapixel video camera. McNutt and his team spread the word through community meetings and presentations at schools. Far-left activists eventually derailed what they labeled the “spy plane” program, despite its success and popularity—polls found three-quarters of Baltimorians approved, with Black residents favoring it most strongly.

“‘Spy plane’ implies secretiveness—I want everyone in the city to know it’s there,” McNutt says. “I want some mom to be able to tell her kid, ‘Don’t you dare, you see that plane up there, it’s going to catch you.’ We want to deter people from committing the crime. It’s ten times more important to deter than to catch.”

In January of this year, St. Louis agreed to a deal with McNutt’s company, which brings the program closer to KC.

Persistent Surveillance Systems ends up costing about four million dollars per year—the Department of Justice says each murder costs society about eight million dollars—often paid for by grants. McNutt says his company can usually arrange funding. He sees the work as a mission, taking the technology he developed to save lives in Iraq and using it to save lives in American cities plagued by violence. “I still have a hard time understanding how we in our country allow this to happen,” he says. The surveillance plane is appreciated by most—but not all—police officers.

“Most cops, when you show it to them, say ‘this is great,’ but you have to remind them: We don’t just investigate suspected criminals; we investigate suspicious police activity,” McNutt says. “We have had two people we actually got released from prison.” —Martin Cizmar

What if a local company develops the future of proof of vaccinations?

IF you’ve already been vaccinated, you probably know that the paper cards issued as proof are a bit of a hassle—they don’t fit neatly in a wallet and could easily be ruined by the washing machine. Well, one KC company is developing a better way, which might end up being the standard solution to this problem.

Cerner, the massive health information company based in the Northland, has created a way to carry proof of vaccination on your phone. “If you’re familiar with Apple Wallet or the Google wallet metaphor, the idea is that you can store certain things in your wallet, maybe an airline boarding pass, maybe a concert ticket, maybe your insurance card, maybe your vaccine record,” says Cerner Senior Vice President Dick Flanigan. “The idea is to give the consumer the control, on his or her phone, of the record of the vaccine.”

How does it work though? The identification will “use the concept of the QR code to quickly validate that you have the vaccination,” Flanigan says. This should prevent fraud, and it will allow your vaccine records to easily transfer from system to system, no matter where you were vaccinated. This technology will debut this summer and could be useful in any future outbreaks, too. —Kathleen Wilcock

What if someone made a safe place to ghost ride the whip?

Maybe it was the closure of nightclubs, maybe empty streets were more inviting, or maybe kids just needed to blow off some steam, but the onset of the coronavirus pandemic coincided with another trend in Kansas City: large groups gathering downtown to drag race and do burnouts.

To be sure, American teens have been doing these things since they had access to automobiles. But the growing popularity of sideshows—informal automotive stunt demos popularized in Oakland—has angered some, given crowds of hundreds have shut down streets in the heart of the city and have sometimes been accompanied by the discharge of firearms.

In late February, Mayor Quinton Lucas floated an idea: What if the city simply opened a sanctioned drag strip and burnout park?

“We continue to look at ways we can enhance our options on drag racing and making sure people aren’t just going out in the street,” Lucas told Fox 4.

Lucas, whose previous gig was law professor, allowed that “liability issues” might be an issue for the city. “We have to make sure everyone is going to be safe,” he said.

It’s perhaps worth noting here how the American Graffiti era ended: Private companies opened drag strips where they charged gearheads and observers a fee, and everyone was happy. —Martin Cizmar

What if the brisket on your Z-Man was made from cellular engineered meat?

Kansas City is a cowtown—we all know that. KC is a national leader in beef production, with a long storied history in the industry. But what if we were able to produce just as much meat without the bloodshed?

In February, Bill Gates told Technology Review that he thinks “all rich countries should move to one hundred percent synthetic beef,” adding that consumers can get used to the taste difference and eventually shift the demand to satisfy the cost. His statement came soon after the government of Singapore approved cellular-based meat, allowing the city’s trendy restaurant 1800 to start offering lab-grown chicken, engineered by San Francisco startup Eat Just, in a trio of sample dishes—bao buns, phyllo puff pastries and their take on chicken and waffles.

To engineer cell-based meat, “We take stem cells and put those into culture, put them with the right variety of chemicals,” says Dr. Ken Odde, a professor at the Department of Animal Sciences and Industry at Kansas State University who previously worked for SmithKline Beecham Animal Health and Pfizer Animal Health. “It’s a genetic engineering process. We can ultimately grow tissue that has some semblance of meat.” The meat is then further engineered with chemicals to more closely match the taste of traditional meat.

Odde says the U.S. is the largest producer of beef in the world. We’ve mastered the craft and need fewer cattle because we’ve created cattle that are feed-efficient and able to grow rapidly with high-quality carcass traits. “In every community, there’s a segment of the market who would look at this, especially if they are convinced that it has a real strong sustainability position,” Odde says. “And I think there’s a segment of the market that would be receptive.”

For cell-based burgers and chicken tenders to show up on local restaurant menus, government approval is required. “That’s a huge challenge for us,” Odde says. “A lot of these companies are forecasting that they could be on the market in a year or two. I used to work in the animal health industry and worked with both the Food and Drug Administration and the USDA in licensing animal health products. Once you really have your evidence, it can still take another three to five years to actually get product approval. —Nicole Bradley

What if somebody bought The Star and turned it into a nonprofit?

The McClatchy Company, owner of The Kansas City Star, declared bankruptcy last year. The paper was then sold to a hedge fund. It’s early to say definitively how that will impact the Star, but we know what’s happened in other cities where hedge funds bought metro dailies: They aggressively cut jobs in an attempt to maximize short-term profits, then discard the corporate carcass once there’s no more cash to squeeze from it. The city is left with a hollowed-out institution no longer capable of keeping its citizens informed.

Of course, the Star has been shedding staff and pulling back its news coverage for years for reasons that mostly have nothing to do with ownership and everything to do with the fact that the business model for a local metro newspaper isn’t working: Print advertising is in rapid decline due to a permanent change in consumer behavior, and the digital advertising dollars that were supposed to offset those losses are being hoovered up by tech platforms like Facebook and Google. Who wants to pay for a subscription when the paper keeps laying off staff?

“The market dynamics have fundamentally shifted,” says Sue Cross, executive director of the Institute for Nonprofit News. “Metro newspapers just don’t function well anymore as for-profit companies.”

Those concerned about the rapid decline of news in Kansas City—particularly those with the means to do something about it—should take a look at Cross’s growing organization, a coalition of outlets from across the country that have determined the only path forward for robust local news coverage is through a nonprofit model. Many of these organizations are located in places that share much in common with Kansas City.

The Philadelphia Inquirer and the Tampa Bay Times are now owned by nonprofit corporations. In 2016, Paul Huntsman, son of a Utah billionaire, purchased The Salt Lake Tribune from the hedge fund that was bleeding the city’s newspaper dry. In 2019, he converted it into a nonprofit and began seeking donations from readers, many of whom have been eager to support newsgathering. In Minneapolis and Boston, benevolent local billionaires have bought the daily papers (for not very much money, it’s worth noting) and invested in them not because the papers are major profit centers for their business empires but because they believe local journalism is an essential component of city life.

The path forward for local daily news in Kansas City is not some sexy new app. It’s simple, really: You need the philanthropically minded to step up, stop bemoaning the condition of the Star and actually do something about it. —David Hudnall

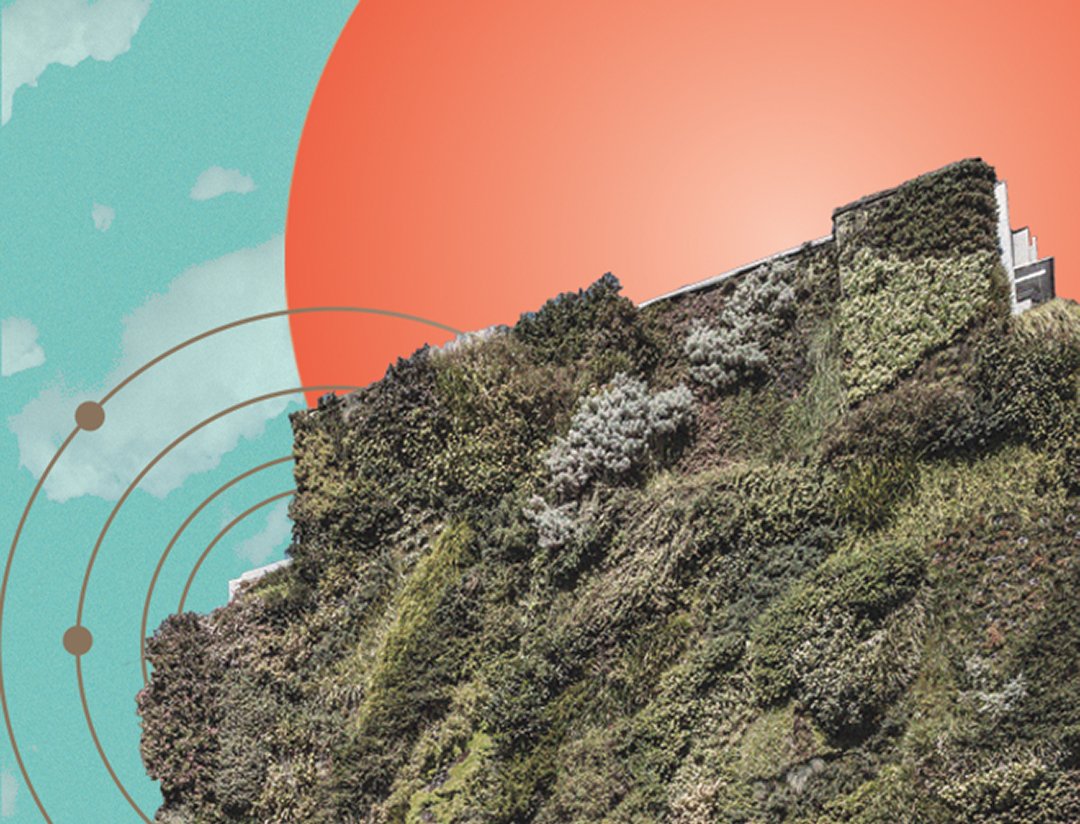

What if the concrete walls on downtown parking garages turned into gardens?

In the heart of Madrid’s arts and culture district is a giant green wall. It’s not just any green wall—it’s a four-story-high vertical garden designed by French botanist Patrick Blanc that takes up the entire side of a former power plant building. According to sustainability blog TreeHugger, the wall houses fifteen thousand plants from more than two hundred fifty different species.

You know those eyesore parking garages, like the beige, concrete slabs taking up blocks in downtown’s Financial District and at Town Center? We looked into whether it’d be possible for KC to take pointers from Madrid to beautify parking garages while also maintaining living wall benefits like cleaning the air, muffling sound and capturing dust particles.

Kurt Kraisinger, founder and president of Overland Park landscape architecture firm Lorax Design Group, says the main challenge that Kansas City—or any city, for that matter—would run into is the sheer amount of maintenance required to support these plant walls.

“The irrigation systems, the plant material and the type of soil that you use in those structures and the growing media have to be spot on,” Kraisinger says. As an easier-maintenance alternative, he suggests using naturally climbing plants more.

“In the Kansas City market, we like to use a lot of vines, like climbing hydrangeas and roses and wisteria,” he says.

That sounds like a lot of work, but we know of at least one local spot that took a shortcut: a fake plant wall on Main Street right between City Club Apartments and the DGX. It could’ve fooled us. —Nicole Bradley

What if we had a marina on the Missouri River?

Most people in Kansas City see the Missouri River as a dirty thing they have to drive over. Our metropolis exists because of the confluence of the Kaw and Big Muddy, but life in our modern city is fully detached from the longest river on the continent. Most people think it’s dangerous or toxic—or both.

Scott Mansker has done a lot to change that misperception as the founder of the Missouri River 340 canoe race from KC to St. Louis. And it’s working. “Having been on the river for thirty-two years now, I’ve never seen more people than I do now,” he says. “It’s definitely happening, and we are headed for a tipping point, and someone could definitely capitalize on that.”

How to capitalize? By opening a marina where people can store and launch boats, get gas and snacks and hang out with other boaters. The ideal marina is on a backchannel insulated from fast-flowing debris on the main channel. All things considered, it’s a relatively small project for a city this size.

“This isn’t prime real estate you’re talking about—this is river bottom,” Mansker says. “It’s not like you have to convince people here to buy a boat. People here have boats; they just don’t know they can use them in the river.”

Mansker grew up playing in a nameless creek in Overland Park, fascinated with the idea that it would eventually end up in the ocean. At age twenty, he and some friends built a raft and spent a week floating the Missouri, Huck Finn-style. “I just was absolutely hooked,” he says. “I just could not believe we were the only people out there. We had it all to ourselves.”

For those who have boats but are concerned about navigating a river, Mansker points out that the information you need to stay safely in the middle of the channel now comes on a cheap app instead of from expensive gear and nautical charts. And modern marinas don’t require building heavy infrastructure with slips for every boat. Instead, today’s marinas store boats “dry stack” style and drop them into the water via giant forklift at the owner’s request. Mansker has taken boat trips from KC to Chicago and the Gulf of Mexico—all much more of a hassle than they should be because of the city’s lack of a marina. Omaha has a marina on the Missouri, as does Columbia—you’ll see people jet-skiing, swimming and tubing on the Missouri in both.

“There’s all these trips you can make in motorboats and see parts of the city very few people see,” he says. “It’s an amazing experience. There’s all kinds of stuff you can do with your boat rather than just drive it in circles on a lake. You can take your boat on adventures to Chicago or Memphis or Mobile Bay or Key West—all these places you can get to in a twenty-foot boat from Kansas City.”—Martin Cizmar

What if there’s a way to get fresh fruit and veggies to underserved neighborhoods while also building wealth?

Max Kaniger doesn’t really care for the term “food desert.” It’s an oversimplification, he says, of systemic issues in our food system. The United States Department of Agriculture defines food deserts as geographic areas where residents lack access to affordable, healthy food. Adding a Sun Fresh to the Linwood Shopping Center doesn’t magically turn the area into an oasis.

“The two big problems in our food system today are waste and access, and they can fix each other,” Kaniger says. The stumbling block is distribution. “It’s getting the right food to the right people at the right price, consistently. And that’s what we do.”

In 2017, Kaniger founded Kanbe’s Markets, a nonprofit food delivery organization. In 2020, Kanbe’s delivered over a million pounds of fresh produce to individuals and their families in underserved neighborhoods. They did it through their Healthy Corner Store program, which partners with convenience stores (forty-one so far) to provide the equipment (coolers), containers (racks, baskets) and products (fresh, local fruit and vegetables) that aren’t readily available. Kanbe’s handles delivery and restocking, then shares the profits with shop owners. The produce Kanbe’s stocks comes from donations from local wholesalers who have excess inventory.

“It’s tapping into an infrastructure that’s already there,” Kaniger says. “But the best and most important part is the connection to the community. A lot of times, the store owners have lived in that neighborhood all their lives and they know people that are coming into their stores.”

Kaniger’s biggest idea builds on that. The current program works, but it lacks a few essential pieces to holistically address food inequality. Beyond location, food inequality is influenced by income, nutritional education and race. To address some of those elements, Kanbe’s Markets hopes to introduce a for-profit franchise model with stores that do more than offer quality produce at affordable prices.

“The franchise model is a separate, for-profit business owned by people in the community,” Kaniger says. “The idea is that it provides ownership, which can help address generational poverty—the same way owning versus renting a home provides a certain security.”

But you wouldn’t be able to buy your way into a Kanbe’s Market franchise store. “The majority stakeholders would be elected by the neighborhood,” Kaniger says. “They’d apply and provide references, and the community would have to vote and say, ‘This is the person that would be best to run this neighborhood institution.’ Their job would be to cultivate the community around it, and then food can do what it’s supposed to—bring people together.” —Natalie Gallagher

What if KCMO’s recycling bins weren’t so junky?

If you’ve driven through a neighborhood in Kansas City on trash day, you’ve maybe taken note of the sorry state of the recycling bins. In KCMO, where recycling pickup is free and unlimited, the black plastic bins tend to be cracked to hell. Sometimes they’re mere shards, held together by weatherbeaten duct tape. The city uses bins made from brittle recycled plastics. According to a city spokesperson, failure is by design.

“The bins are not expected to last more than one to three years, so if you get more shelf life out of the bin, you are doing great—especially with our severe winters when extreme cold can make the material brittle and easily broken,” says John Baccala, spokesman for the Neighborhoods and Housing Services Department.

But what if there was a way to make it so that the city’s neighborhoods don’t look like Robocop’s Old Detroit on trash day? In Canada, where frigid temperatures strain bins, a company called Nova Products makes bins that last “many years” from durable high-density polyethylene. They come with a five-year warranty.

“If [Kansas City’s] bins are falling apart and the residents are continuously required to purchase new bins, this may deter some from participating in the recycling program,” says Nova’s sales and marketing manager Kayla Kleber. “The goals of most recycling programs are to encourage participation, and a major factor is to make it easy for the participant, so perhaps revisiting the needs of the residents is something to investigate. —Martin Cizmar