You’re really not supposed to knock someone’s block off outside of a boxing ring, according to longtime local boxing legend John Brown, who listens to his own advice most of the time.

The beloved boxing trainer at KCK’s Turner Recreation Commission community center certainly wouldn’t advise any of his fighters to use their skills to harm others outside the ring. If they do, they’ll be in trouble.

However, Brown, 77, does make one exception to his no fighting outside the ring rule, and that’s dealing with bullies. But even then, Brown, who grew up in South St. Louis and was teased for having a cleft lip, advises holding back until there’s really no other option than to retaliate. “You win, you still go to jail,” he says.

Just a few days before this interview, Brown had to hold himself back, he says. An irate driver had cut him off and was approaching Brown’s car on foot, screaming. Brown got out of his car to see what the motorist wanted. “I say, ‘Stop where you are,’” he says. “‘I might feel threatened here. Bad things are gonna happen, you know?’”

Brown is one of those naturally affable yet very capable-looking people who you’re afraid to even imagine seeing pissed off. He has white hair, a square jaw and, despite his bad knees, an unwavering gait. The guy left, and Brown didn’t break his rule—this time.

There is nothing the Shawnee resident—who trained the KC metro’s last world boxing champion 30 years ago, the late former heavyweight Tommy Morrison—cares more about than his boxing kids.

On many Saturday nights, you’ll find quite the boxing scene in KCK’s Turner neighborhood, when the popular recreation center on South 55th Street transforms into Turner Boxing Academy’s Fight Night. April 13 was one of those nights.

Looking like a smaller version of a boxing match at MGM Grand or Madison Square Garden, Fight Night inside Turner’s brick gym can be disorienting for first-timers. The windows are blacked out and the interior is transformed into a bumping, almost club-like atmosphere, with loud music, merch tables and concessions surrounding a professional boxing ring.

Some attendees are dressed to the nines while others are busy, frazzled parents of fighters and boxers. With the action spilling outside onto the street, it resembles a block party with food carts. The coffee shop across the street, The Windmill KC, stays open late.

Brown is at the center of it all, the event’s showrunner. He smiles broadly in a Turner T-shirt as he poses for pictures with fighters, both girls and boys, who just withstood 19 bouts. Boxers representing teams from all over the area, including as far south as Wichita, stand with their bulky golden belts, just like the pros after a big win.

One such fighter that night was Artem Lepekha, a 17-year-old Ukrainian student attending Olathe East High School. He fled the fighting in Ukraine with his family earlier this year thanks to help from a local friend of his mother.

A participant in the 195-pound weight class, Lepekha gots a cut above his eye, prematurely ending his fight. But Lepekha, a determined offensive fighter, wasn’t deterred by the loss. His goal is to make a mark in professional heavyweight boxing, and there’s little question whether the journey from Ukraine to Turner was worthwhile for the young pugilist’s future. Lepekha already considers Turner his “team,” and calls Brown a “very good coach.”

Brown’s been self-funding the boxing program at Turner since creating it 16 years ago, and fight nights are now in their 12th year. The trainer estimates about 10,000 kids have come through the program’s doors, and he’s helped coach them all and place them in tournaments.

Brown pays for the bulk of Turner boxing’s operations out of his own pocket, including fighters’ flights and hotel rooms so they can compete at events across the country—because he can. Unlike many trainers, Brown found success outside the ring, too.

Everlast is likely the most-known boxing-associated brand on the market, but one of its close competitors, used by thousands of men and women in gyms around the world, is an apparel and equipment company called Ringside, which Brown founded in 1978. What started as a four-page catalog soon became “the goose that laid the golden eggs,” as Brown puts it. He sold the Lenexa-based company in 2012, but it has allowed him to fund his true love: training boxers.

Brown named his company Ringside after the St. Louis club where he learned how to box as a kid after getting teased and beaten up for his cleft lip. At Ringside, he fell in love with the gym’s mostly African American boxers. He gets tearful when recalling how at home they made him feel. “It was terrific that people just treated me so well,” he says. “I just fell in love with the sport.”

Brown’s recalling of his past comes from his detached home office, a sort of man cave gazebo that’s filled with boxing paintings and photographs. The adjoining deck overlooks a peaceful pond, very far away from the sweaty, rhythmic, chaotic orchestra of boxers pounding away at bags.

Brown is on the cusp of taking another local and extremely talented boxer, Marco Romero, pro. The potentiality has caused Brown to reflect on Morrison, who Brown trained 30 years ago. The boxer’s insatiable appetites and wild behavior were eventually his undoing.

Brown says he told Morrison that if he would “have sex with one woman a day instead of five and stop doing drugs and alcohol, we’ll make $100 million.” Despite beating George Foreman, becoming the World Heavyweight champion and a earning role in the film Rocky V, Morrison’s career eventually faltered. An HIV-positive diagnosis came in 1996 and he succumbed to complications from AIDS in 2013.

After his time with Morrison, Brown shied away from professional boxing and stayed focused on amateurs. He was the president of USA Boxing, which oversees the Olympic boxing team, from 2015 to 2019.

“I could make you wealthy and keep you healthy” is what Brown says to fighters who want him to make them pro. “If you have a lifestyle that can’t keep you healthy, I won’t be involved in that.”

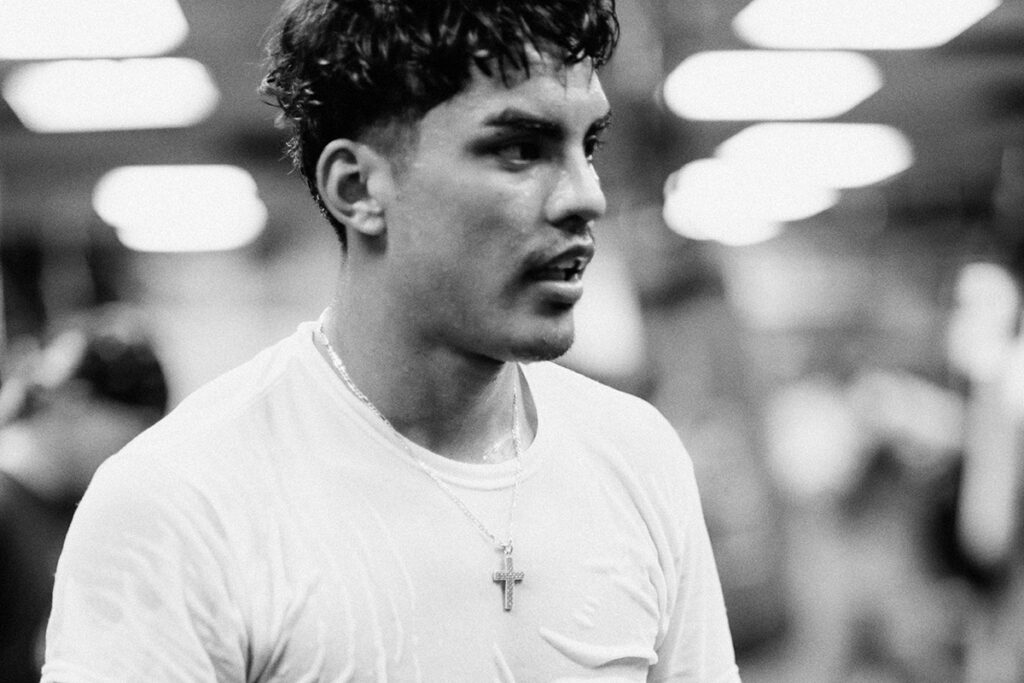

But Brown has once again decided to jump into the professional boxing world with Romero, a recent Olathe West High School graduate, his latest protege. The 18-year-old middleweight will make his professional debut this summer.

Romero missed his graduation ceremonies to fight in the 2024 amateur Detroit Golden Gloves National Tournament of Champions, where he won the National Golden Gloves title in the 165-pound class, his last as an amateur. He has amassed 18 national non-professional titles.

This June will mark Romero’s first professional fight, where he will compete as part of the Father’s Day Pro Boxing Classic at Cross Insurance Arena in Portland, Maine.

Romero, who often sports a megawatt smile, intends to bring a pro boxing title back to the Kansas City area within five years. “I’m hoping to be able to bring a world championship back home and be an inspiration to all the kids here in Kansas,” he says.

The last time a world boxing championship was associated with the metro was 1993, when Morrison won the World Boxing Organization heavyweight title with Brown in his corner against Foreman.

Guiding Romero toward boxing greatness might not be such a long shot. The 18-year-old is immensely talented and likable. Brown says, half-jokingly, that Romero was raised by such a supportive family and has such an affable demeanor that he might not have enough meanness to become champ.

But whatever happens, peer Bruce Silverglade is bullish on Brown’s return to professional training. The owner of Gleason’s Gym, in Brooklyn, New York, where champion fighters such as Muhammad Ali, Roberto Durán and Jake LaMotta all trained at some point, estimates that he’s known Brown for 45 years—maybe not as the closest of friends but certainly as consistent acquaintances. Silverglade, also 77, can relate to Brown’s determination.

“I love running my gym, and John loves training,” Silverglade says. “When you’re a boxing guy and it’s in your blood, you never want to give it up. To have John say, ‘Hey, I’m going to jump back in,’ I absolutely wish him all the luck in the world.”

Turner Boxing Academy Fight Nights

Friday Fight Nights at the Academy (831 S 55th St, KCK) start at 5 pm. Admission for bleachers is $10, $15 for floor.

The year’s remaining Fight Nights are:

June 8

July 13

Sept. 7

Oct. 26

Dec. 7