“As you well know, a record must break on radio in order to actually make a living for the artists involved. Up until now, you’ve had to make these decisions on your own relying on perplexing intangibilities like taste and intuition. But now, there’s a better way. The cut that follows has been analytically designed to break on radio…”

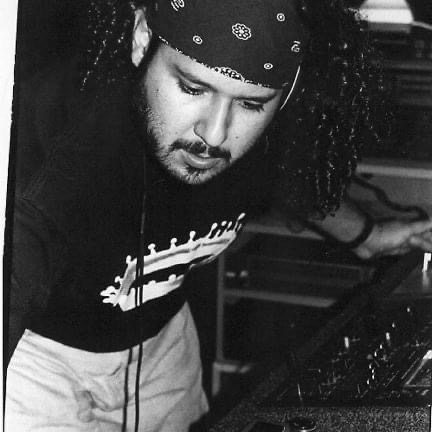

In the dim and slanted afternoon light of Ray Velasquez’s “subterranean suburban bunker,” the spoken word intro from Negativland’s Escape From Noise gives way to a song called “Paradise Engineering” from the 2019 debut by techno artist Sam Barker.

“This is what I’m thinking about as an opening for the first show,” says Velasquez. “I want to integrate a lot of spoken-word, which is something I’ve done in my DJ sets—but I don’t want to be too obvious about things.”

It’s all sort of perfect. Too on-the-nose, perhaps. A few days later, when Velasquez’s groundbreaking and wildly influential radio show Nocturnal Transmission makes its triumphant returns to the airwaves via Kansas City’s 90.9 FM The Bridge after a twenty-year hiatus, the Negativland segment is tucked deep into the show, at the start of the third hour. It’s followed not by “Paradise Engineering,” but by a shimmery, pulsing trace track called “Rez” by a Welsh trace duo Underworld, released as a b-side in 1993 and now regarded as a classic in the genre.

If you’ve dipped a toe into the avante-garde side of local radio, or to electronic music, over the past forty years, you’ve probably heard a set by DJ Ray Velasquez. Velasquez started as a DJ back in his days at KU’s Oliver Hall and went on to be a stalwart on the beloved and much-missed Lawrence-based new wave station 105.9 KLZR. He’s the type of DJ whose radio shows from thirty years ago get uploaded to YouTube after someone finds bootleg copies on cassette tapes in their attic.

Though he’s a fan of everything from power-pop to honky tonk, Velasquez’s specialization in electronic music from its earliest days has taken him to World Cup parties in Brazil and the beaches of Israel. It also, famously, found him DJing the funeral of beat icon, and late-life Lawrence resident, William S. Borroughs.

“I get it all the time: ‘You changed my life,’” he says. “Which is an amazing thing to hear. But it makes sense because music is really what changed that life. It wasn’t me. It was music that did. And music changed my life.”

Ray Velasquez was born in Kansas City, Missouri at the start of the sixties and grew up in Overland Park. His dad was a record-hound, and as a young child, his dad would take him to the old Katz Drugstore to buy 45s. After twelve years of Catholic school, he graduated from Bishop Miege at the end of the seventies and enrolled at KU.

At KU, culture varies widely by residence hall—he ended up on the ninth floor of Oliver Hall, where he was named Social and Cultural Director. Though he made an effort to understand what the other kids were into—he went with classmates to see Rush and Jerry Jeff Walker— he was bullied by classmates down on the seventh floor, who subjected him to repulsive pranks and graffiti calling him a “punk rock f—–.”

“I was hated so much at Oliver Hall by these guys,” he says. “I just kept programming great stuff, and just kept pissing them off.”

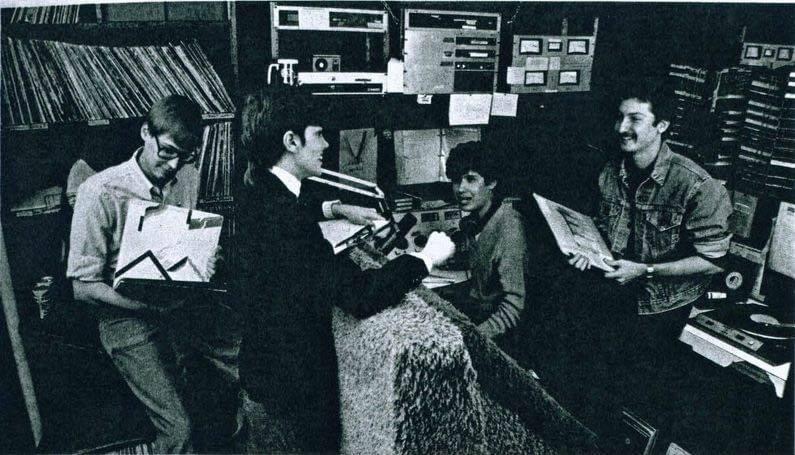

Velasquez found his tribe at KU’s 90.7 KJHK, a classic college rock station operating on the “radio lab” format-free model. The station had an industrial music show on Sunday nights called The Debraining Machine, that played stuff like Throbbing Gristle and Coil. That show went on hiatus in the summer of 1983, and Nocturnal Transmission was born.

“It was the kind of show where I would do very strange things, like play film soundtracks—Vangelis, but not cheesy, stupid Vangelis,” he says. “Bits of things from Blade Runner, which I still do. The whole thing at the time was head music, as opposed to body music. I would also integrate acoustic music, like Paul McCartney’s ‘Junk’ from the first solo record. Or maybe ‘Old Friends,’ by Simon & Garfunkel and then go into something electronic that was warm and sad and sweet. I didn’t know that this is what I was trying to do at the time, but I was trying to create an emotional narrative.”

Creating a narrative is the buzz in DJ circles now—aspiring DJs can enroll in a Master Class by Quest-love of the Roots and The Tonight Show to learn all about it—but it’s not something that was talked about until recently. When Velasquez started playing the downtempo electronic music that would go on to become the foundation of chill-out culture at raves there was “no definition” for what he was doing.“ It came naturally to me,” he says. “I didn’t know at the time that’s what I was doing, but I later realized that’s what I was doing. The only thing I want people to take away from the show is the emotional content. It’s not about genre or anything, it’s all about the emotional content.”

Velasquez stayed in Lawrence for a long time working at KLZR, a station named one of the ten best in the country by Rolling Stone during his tenure. Velasquez was a fixture in the city’s culture, perhaps best exemplified by being asked to spin records behind the casket of legendary beat writer William S. Burroughs during his 1997 funeral services in Lawrence. (Velasquez opened the set with Ry Cooder’s brooding “Paris, Texas.”)

The family that owned KLZR sold it to a company that turned it top forty, a move that inspired pickets and bumper stickers, but didn’t bring down the Backstreet Boys or Britney. Ray moved to New York in 1999, to the Carroll Gardens neighborhood of Brooklyn. He kept producing the show until the new ownership dropped it in 2003.

“I lived in Lawrence forever—twenty years in Lawrence,” he says. “Which prepared me for New York. When I moved to New York, everyone thought I was from New York. I thought that was hilarious. When I left here, people said to me, ‘Oh you’re going back home?’ No, I’m from here!” Velasquez does have a Big Apple swagger and speaks with the coffee vowels you might find in Hempstead.

“I learned it all from the movies,” he says.

The great irony of Ray Velasquez’s career is that while one of his worlds—terrestrial radio—has collapsed, the electronic music he’s made his name knowing has become a cultural force. That was almost unimaginable when he was hanging out at the legendary SoHo discotheque Paradise Garage in the summer of 1983 as a band called New Order came in to perform the song “Confusion” live for the first time. Or when he saw a club kid fresh from the Detroit suburbs perform on the roof of a club called Danceteria. He remembers handling the heavy European-pressed twelve-inch single from a group called Daft Punk in the mid-nineties.

“I remember the future,” is how Velasquez puts it.

The thing about the counterculture is, while it has brief periods of ascendance, such as the late sixties or early nineties, more often than not it’s subsumed back into the mainstream. Disco and House music largely started in gay and Black dance clubs in Chicago and New York during the era of Debbie Boon and Eric Clapton. In the middle of the noughties, the culture shifted with the rise of sub-genres like dubstep that were embraced by the same demographic that once bullied Velasquez at Oliver Hall.

“At the very start I didn’t mind EDM—me and the people I knew gave it a chance,” he says. “It’s just a name that’s become a sound, and that sound is cheesy and cheap and stupid. If you’re going to encourage douchebaggery, I don’t want to be part of that… When Katy Perry has an EDM record out, it’s novelty music to me. EDM is to Techno as Olive Garden is to Italian food. It makes my skin crawl because it’s so incredibly insincere.”

He’s still working through his artistic response. “I’m thinking about doing a DJ set—I’ve been working on it in my head for about a year—called ‘Parasites, Posers and the Rise of the Roid Boys’ and it’s about these pretty boy DJs that play EDM, and they have the right headshots and they wear the right clothes—very handsome, thick-neck, roid boy guys. I’m thinking of doing a DJ set that makes fun of that, hopefully using quality music. I already have this fun spoken-word piece called ‘How to Become a DJ’ to work into that—it’s been in my head for a year now. I just can’t seem to get it down.”On the other hand, it’s gratifying for Velasquez to see DJs be treated as artists in their own right. Back in the early eighties, he says, he foresaw a world where there were superstar DJs who drew crowds eager to experience their sensibilities and collections.“

It’s my job to not be a jukebox, but to seduce the public,” he says. “I used to aspire to be the Beatles of DJs. Now, I’m perfectly content to be the Lester Bangs of DJs.”

And yet, anytime a man stands behind turntables, the requests will come. On one memorable occasion, Velasquez was approached by a swarthy fellow who identified himself as “one of the investors” in a swanky new New York club he’d been hired to play, asking him to play Journey.

“I said, ‘That’s not really what I was hired to do,’” Velasquez says. “He said, ‘Look man, I want you to play Journey, I’m one of the investors.’ I said, ‘Well then you should be grateful that I’m not going to play Journey—because it will fuck up your brand. What is this, a bowling alley now?”