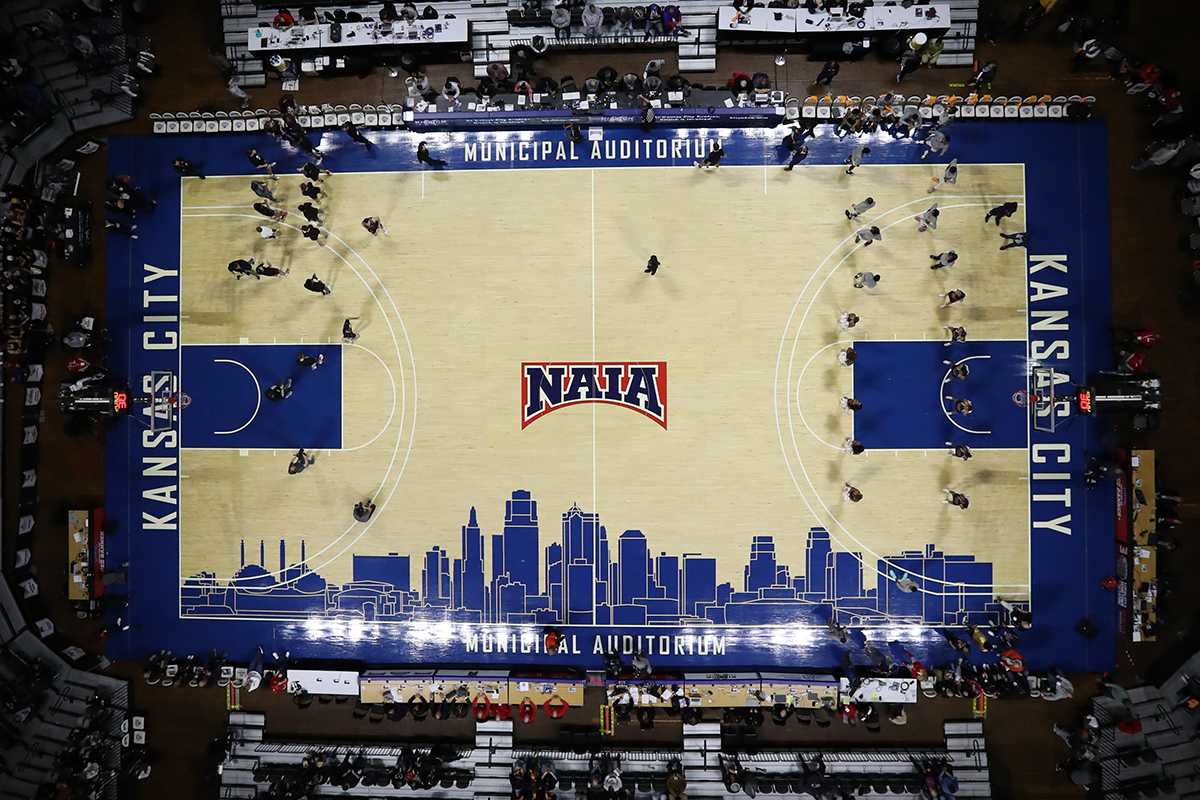

Headquartered in KC, the NAIA has been the governing body of small college athletic programs for more than 80 years

The NAIA’s men’s basketball championship tournament heads to KC’s Municipal Auditorium this March

LITTLE did the inventor of basketball James Naismith know when he and his cohorts started a KC college basketball tourney some 87 years ago that it would spawn a national athletic association representing more than 83,000 college students.

But that’s exactly what happened.

Since 1937, with the exception of just a few years, Kansas City has played host to a national college basketball tournament. Although the name has changed over the years—at first called the National Intercollegiate Basketball Tournament—by 1952, it had evolved into more than just an annual men’s basketball tournament. The National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics started slowly representing more colleges and sports and became the first student sports organization to invite historically Black institutions to join, just a year after its inception. Fast forward to now, the NAIA counts 237 mostly small universities and colleges as members and has students playing dozens of sports, such as football, golf, tennis, track and field, and baseball.

This year, the 87th NAIA Men’s Basketball Championship will be held March 20–25. The participating teams are winners of regional games from across the nation. They will play 15 elimination games for a chance at the title at Municipal Auditorium.

The tournament will do what it’s always done for the city—welcome thousands of visitors from large and small towns across the country, jam hotels and restaurants and create a local and national buzz about games and players that can change lives.

For tournament and ticket information head to naia.org or scan here.

Impact of NAIA championship game on Kansas City

$2,700,000

Estimated

city-wide revenue

2,500

Athletes participate

in the tourney

40,000

Fans descend on the metro to

watch their favorite teams

The NAIA vs the ncaa

There’s a difference, and it’s more than just numbers

Although the basketball celebrations will go on throughout the city, there is a national college sports evolution underway for student-athletes. It’s not the same game anymore. The NAIA and the larger National Collegiate Athletics Association are both dealing with new issues, such as managing athlete branding and how to address athletes identifying as transgender.

“The NAIA is the way college athletics was meant to be,” says Jim Carr, CEO of the NAIA. “We based ourselves on character-driven intercollegiate athletics. We’re building people of character for life through intercollegiate athletics.”

It’s commonly understood among both NAIA and NCAA officials that the larger universities and colleges that are a part of the NCAA usually offer a student-athlete a broader, and some say better, sports experience, usually led by a stronger and better-paid coaching team.

NCAA college Ohio State spent nearly $300 million on their sports programs in 2023, a new record, and made a profit of $4.6 million. Coaches at NCAA teams can make upwards of $10 million a year, some with half-million dollar performance bonuses.

For the most part, the NCAA represents big colleges and universities. The association is made up of 1,100 schools, with nearly 540,000 student-athletes who compete in more than 19,000 teams annually.

Parents often see the NCAA as presenting a clear pathway for their son or daughter to head to the pros. Yet even information on the NCAA website points to the slim chance of any student-athlete making the professional ranks. Of the nearly 20,000 NCAA men’s basketball players, only 1.1 percent go pro.

The NAIA argues that going pro shouldn’t be the primary factor in deciding the future of a student-athlete. They focus more on what is going on in a teenager’s personal development outside of sports and are going for a more well-rounded student.

To be sure, there are NAIA students who have gone on to play pro, Carr says, but not very many. “There’s a very remote chance of that,” he says.

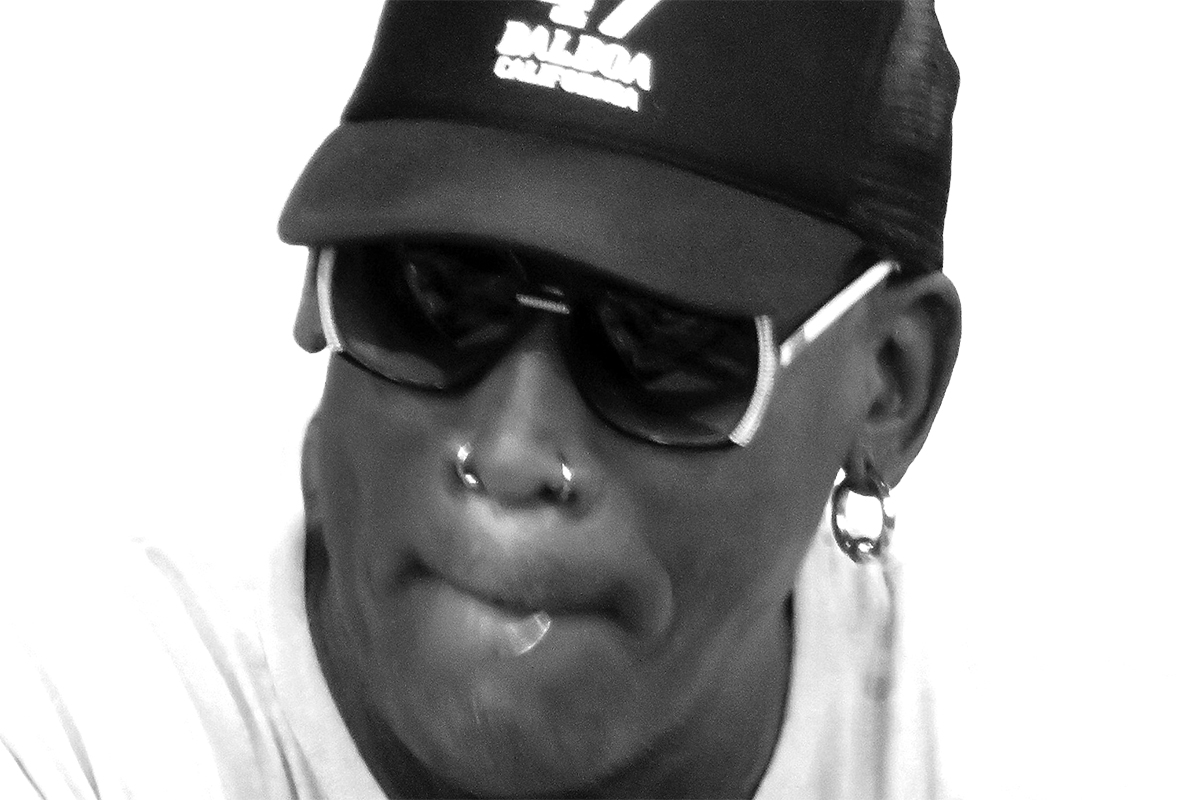

Dennis Rodman is one NAIA student who went pro. He attended the NAIA school Southeastern Oklahoma State University in Durant, Oklahoma, where he was a three-time All-American and led the NAIA in rebounding his junior and senior seasons. He had a stellar pro career with multiple teams, ending with the Dallas Mavericks in 2000.

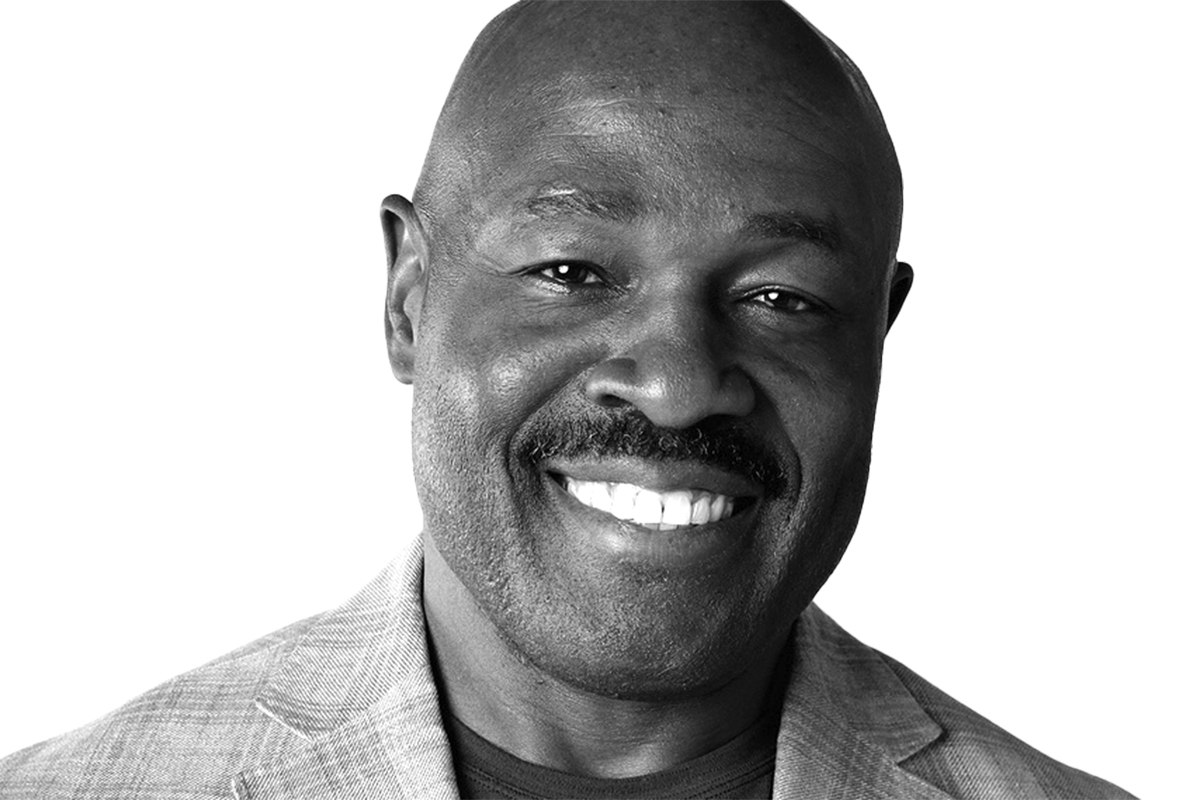

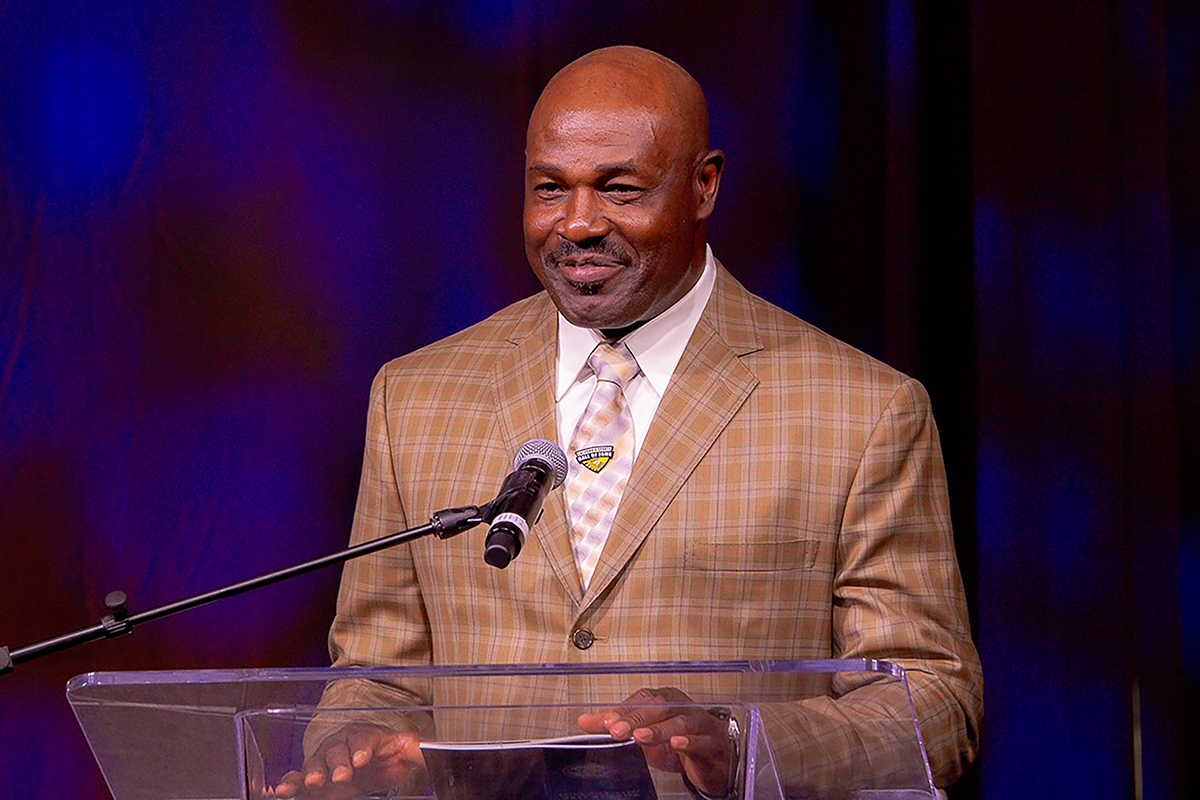

Kansas City Chiefs running back Christian Okoye, an NAIA hall of famer in track at Azusa Pacific University in Azusa, California, 25 miles east of Los Angeles, credits the NAIA for guiding his professional football career. “Going to an NAIA school helped me because I never played football before,” he says. “If I had gone to a big school, they probably would have just held me back. But going to a small school, they helped me out a lot by teaching me and being patient with me during my learning.”

The NCAA has addressed the issue of smaller schools coming into the fold. That was one of the reasons for developing NCAA’s Division III, which stressed a more academics/sports balance for this division of mostly private schools with a class size as small as 300. About 40 percent of all NCAA student-athletes compete in Division III.

But there is something different about NAIA schools, in part because most of them are small and faith-based but also because of the students’ relationships with their coaches.

For instance, Okoye still stays in touch with his coaches today—Terry Franson, his track coach, and Jim Milhon, his football coach. “They were like my father to me because my father lived back in Nigeria,” he says. “They stepped in to help me. We talk about life, just everything.”

The size of some of the schools in the NCAA—up to 30,000 students—can mean coaches find more success developing a marquee player from a larger pool of student-athletes, some who will go on to fame and fortune as a pro. That player can draw a crowd and bring in real revenue to a college program.

Size and success like that can also mean that the everyday good student-athlete at an NCAA school who just wants a chance to showcase their talent might get limited play time with their team.

That is, if they get to play at all.

“In some ways, yes, that is true,” Carr says. “Take Baker University compared to the University of Kansas. Most athletes will have a much better opportunity to play at Baker than they would at KU. But if you compare any NCAA Division II or Division III team, it presents a pretty comfortable playing atmosphere.”

FIVE FAMOUS NAIA PLAYERS

Dennis Rodman

Southeastern Oklahoma State University Rodman was a three-time NAIA All-American who led the NAIA in rebounding twice. He played for the Detroit Pistons, San Antonio Spurs, Chicago Bulls, Los Angeles Lakers and Dallas Mavericks.

Christian Okoye

Azusa Pacific University Okoye won seven college titles in the shot put, discus and hammer throw. He went on to play for the Kansas City Chiefs from 1987 to 1994.

Scottie Pippen

University of Central Arkansas Pippen’s pro career took him to the Seattle Supersonics, Chicago Bulls, Houston Rockets and Portland Trail Blazers. Pippen was a seven-time NBA All-Star.

Paul Splittorff

Morningside University Splittorff pitched for the Kansas City Royals from 1970 to 1984. He was inducted into the Royals Hall of Fame in 1987.

Buck Buchanan

Grambling State University Buchanan played for the Kansas City Chiefs from 1963 to 1975. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1990.

Divisions

In 1973, in an effort to bring in smaller schools, the NCAA went from being just one division to three divisions—I, II and III—divided by a school’s student population size. “That was a time when a lot of schools really tried to figure out what to do because now there were other opportunities under the NCAA umbrella,” Carr says.

There was a lot of moving back and forth between the two organizations in the ’80s and ’90s, Carr says, and things “kind of settled out in the 2000s.”

“I think our members who are with us now don’t aspire to be in the NCAA,” Carr says. “In fact, if they move over to NCAA Division III, it’s not necessarily seen as a step up. Sometimes it’s geography-driven. Sometimes it’s more about whatever conference they’re in. We’re also seeing a number of schools transition from the NCAA over to us. So there is some fluidness happening.”

Sometimes a strong NAIA team will transition over to a NCAA Division II, and conversely, the NAIA will bring a couple of NCAA Division III schools over to it.

Okoye’s school, Azusa Pacific, transitioned to an NCAA Division II school in 2012. Right now, Carr says, seems to be another time of transition, whether it’s schools changing associations or student-athletes transferring to NCAA schools at higher rates. “So there’s some uncertainty going on now,” Carr says. “But for the most part, I think that works to our advantage because we are now in more conversations within schools about what would it look like if you’re in the NAIA. And then we mention some of the advantages.

“We have a number of schools we think would probably be better off in the NAIA, so we’re interested in talking with them,” Carr says. “In that respect, we’re more like competitors.”

Among the organization operatives in both the NAIA and NCAA, there is a sort of collegial feeling, a sense of working toward the same objectives in a competitive environment.

For example, NAIA and NCAA officials are currently working through a new transgender policy. “We met probably once a month with the folks over at the NCAA who were working through that,” Carr says. “It’s a really complex issue, but that was a good example of us working together.”

There are sometimes subtle differences in the way an NAIA game is played and an NCAA game is played, which can be good or bad, according to student-athlete Zachery Terpstra, an accounting and finance major who has been playing soccer for four years at Trinity Christian College in Palos Heights, Illinois, just south of Chicago. “I have a friend who played basketball at an NCAA school,” he says. “I asked him about the difference between NAIA and NCAA play, basically comparing the NAIA to a NCAA Division III school. He said the style of play was very similar. He says it’s just a lot different, not easier and not harder. He said that the NAIA offers a lot more variety of play style. NCAA Division III was a lot more hard-nosed, driving into the post, stuff like that.

“The big thing that drew me to NAIA school,” Terpstra “says was their ability to offer different scholarships for athletics, which were not just, ‘Hey, we think you’re a good player, [but] here is money to play, [too].’”

NAIA student-athlete Rachel Watson has been playing volleyball at Waldorf University in Forest City, Iowa. She says that when she was being recruited in high school, she was thinking that she only wanted to go to NCAA Division I or Division II schools. “Big-name schools,” she says. “Now that I’ve been at an NAIA school for four years, I wouldn’t trade it for anything. I know that they care about me. I’m more than just a number or an athlete. They care about me as a person.”

Watson, like many NAIA student-athletes, has other goals in her future than pursuing professional sports. She may coach volleyball after her upcoming three-year stint in grad school, she says, just to stay connected to the sport. “The NAIA has the Champions of Character program (a program to guide students in five core values), something I never really knew about going into the sport,” she says. “But now that I do, it’s a big focus while I am playing volleyball. That is a big part of developing you as a whole.”

Emily Till, a junior basketball player at Arizona Christian University in Glendale, Arizona, says that NAIA schools are able to compete with NCAA schools. Her team made it to the 2023 NAIA national tournament. They are ranked 20th in the country. In her sophomore year, she set a school record for rebounds in a single game (20).

“Honestly, the NAIA is still very competitive, and I think sometimes it gets put out as, like, a lesser level than the NCAA,” she says. “But we can compete with NCAA Division II and Division III teams, and we’re very comfortable with them. In late November, my team went out and played two games against Chaminade University, which is a NCAA Division II school. It’s still highly competitive. But there is more emphasis on the academics part. You are a student-athlete rather than an athlete-student, which I really appreciate.”

Organization Stats

NCAA

The NCAA has three division levels: Division I, Division II, and Division III. There are 352 Division I schools, 313 Division II schools and 434 Division III schools.

About 190,000 student-athletes compete at the Division I level. More than 130,500 student-athletes compete in Division II and Division III.

NAIA

There are approximately 237 member schools in the NAIA. The schools all operate within one division rather than three—a change made in 2020 to provide a balanced and competitive landscape for smaller colleges.

Most NAIA schools are in the continental United States, with some in British Columbia and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

NAIA schools offer 27 sports, with a minimum of six per institution

Over 83,000 student-athletes participate in NAIA athletics.

Student-athlete branding in the digital age

With the onslaught of social media, a hot-button issue for any student-athlete—at both the high school and college level—is branding: developing and controlling their name, image and likeness profile.

A spokesperson for the NCAA wrote in response to emailed questions that they fully support student-athletes profiting from their name, image and likeness and in August launched a platform designed to connect student-athletes with potential service providers, facilitate disclosures of NIL activities and provide insight into evolving trends with the NIL environment.

This follows a new ruling by the NCAA Division I council in April that member schools would be able to increase NIL-related support for student-athletes, including identifying NIL opportunities and facilitating deals between student-athletes and third parties.

To get school support for their NIL activities, student-athletes will be required to disclose to their schools information related to any NIL activity equal to or greater than $600 in value no later than 30 days after entering or signing the NIL agreement.

Meanwhile, the NAIA identified the NIL issue early on. “We were out a little bit ahead of NCAA on the branding issue,” Carr says. “The way I think about it is there were all these restrictions in both associations placed on student-athletes based on pretty archaic notions of limitations that student-athletes should have, and they were perceived to give schools a competitive advantage,” he says. “All the rules for a long time were based on trying to create a level playing field, which was a little bit of a pipe dream anyway.”

What the NAIA did was try to put their student-athletes in a similar position to any other student on campus who has a special talent, Carr says. “So if you think about a musician, a kid who is a really good trumpet player, that student can go out and give trumpet lessons to kids in the community. He can say that he is in the orchestra at whatever NAIA school, so your son or daughter should come learn from him. Well, we saw that a baseball pitcher, for example, didn’t have that same freedom to do that. There were restrictions on going out and saying that you are pitching for school X and therefore you should be able to have your son or daughter take pitching lessons from me.”

There were other things around NIL, such as being able to take money from companies for doing things on social media. It’s worked out well. “We’ve got students who are making sort of the high end, a few thousand bucks, and hardly any of our students are getting full scholarships. So it helps to pay for the rising cost of education or give them some meal money on the weekends or whatever they want to use it for.”

Colleges with both the NAIA and NCAA realize revenue returns from their student-athletes—some NAIA schools can generate up to $5 million from a team. So yes, it’s a numbers game. But it’s also a heart and soul game.

CHRISTIAN OKAYE

ZACHERY TERPSTRA

RACHEL WATSON

EMILY TILL

The NCAA and the NAIA’s curious KC connection

Five years after the NAIA was officially formed in 1952, it opened a KC home office. The NCAA, which dates back to 1906, was formed to regulate the very brutal sport of college football at that time. In 1904, 18 college football players died playing the game. The NCAA’s first official home was in Chicago, where it shared office space with the Big Ten Conference. In an effort to maintain impartiality within the membership, in 1952, then-NCAA executive director Walter Byers moved its national headquarters to his hometown of Kansas City. The organization had several offices while in the KC metro. However, in 1997, the NCAA moved its headquarters to Indianapolis.