There’s a line in the iconic film Selena when Edward James Olmos, who plays Selena’s father, is in the driver’s seat of the tour bus, careening down the highway. He’s on one of his many surly soliloquies, this one expounding the burden of being an American citizen with a Latin heritage: “Being Mexican- American is tough… We have to be more Mexican than the Mexicans and more American than the Americans, both at the same time. It’s exhausting!”

I remember watching this movie when it came out in 1997. I was about nine years old. One year earlier, my family—my Latina mother, my Irish-German father, my younger sister and brother and I—had moved from Texas to a secluded Amish valley in rural Wisconsin, near the small town where my father was born. Wide-brimmed straw hats replaced the cowboy hats I was used to seeing, and it wasn’t uncommon to pass a horse-drawn buggy on the road.

Years later, that scene from Selena would swim to the surface of my mind as I would get pan dulce from Mercado Central around the corner from my apartment in Minneapolis, where I went to college. It’s a colorful indoor Latin market where you can get your hair cut, pick out leather cowboy boots and gorge on the best two-dollar carne asada street tacos in the city. I wouldn’t be quick enough with my Spanish, my accent would be off or some colloquialism would go over my head, and just like that, the woman packaging my empanadas de piña would switch to English. I’d feel outed, like a fraud. Not Mexican enough.

This line would come to me at other moments, too. When I graduated high school, my parents threw a graduation party. We served enchiladas, rice and beans. My mother balked at the need to put out sour cream, a customary condiment for Mexican food in that part of the Midwest. When my paternal grandmother accompanied our family on a trip back to Texas, where my mother was born, she sat in the dining room of my Uncle Mingo’s home in Angleton, staring at a taco in confusion: “How do I eat this?” she asked. My maternal grandmother, Lucy, did not pull her punches. “You pick it up and put it in your mouth!” she said, cackling, elbowing me in the ribs. Not quite American, then.

In college and for a decade after, I waited tables at restaurants. When I was serving, several guests—intrigued, I suppose, by my hair or complexion or lipstick or ability to correctly pronounce Spanish words—felt entitled to ask me, “So, what are you?” I knew what they were getting at, and despite the impudence, I never quite knew how to answer.

I’ve carried this multidimensionality—this confusion—for as long as I can remember. Where do I fit? What am I allowed to call myself?

Once, when I was in eighth grade, I attempted to stake my identity. In the name field on a quiz, I wrote: Natalia Torres Gallagher. I’m pretty sure the dot over the “i” was a heart. Later, when the teacher handed out the graded papers, my name had been crossed out in red, and underneath it she had scrawled a note: “Use real name.”

Natalia is what my mother called me. Torres was her maiden name, before she married and became Lorraine Gallagher. At fourteen, I didn’t know how to defend this. It would take a couple decades—and the death of my mother—to understand that no permission is needed. The realization came abruptly one evening as I stood over the stove in my mother’s kitchen, making the Mexican rice that had been a weekly dinner staple: My name is Natalie Torres Gallagher. I haven’t always used it, but that has always been my name.

I’m not Mexican: I was not born in Mexico. Mexican-American isn’t right, either. I have no connection to Mexico. For as far back as anyone remembers, my mother’s family—descendants of Mexican immigrants—have lived in Texas. My maternal great-grandparents were both born in or around Victoria. My great-grandmother Micha never learned English.

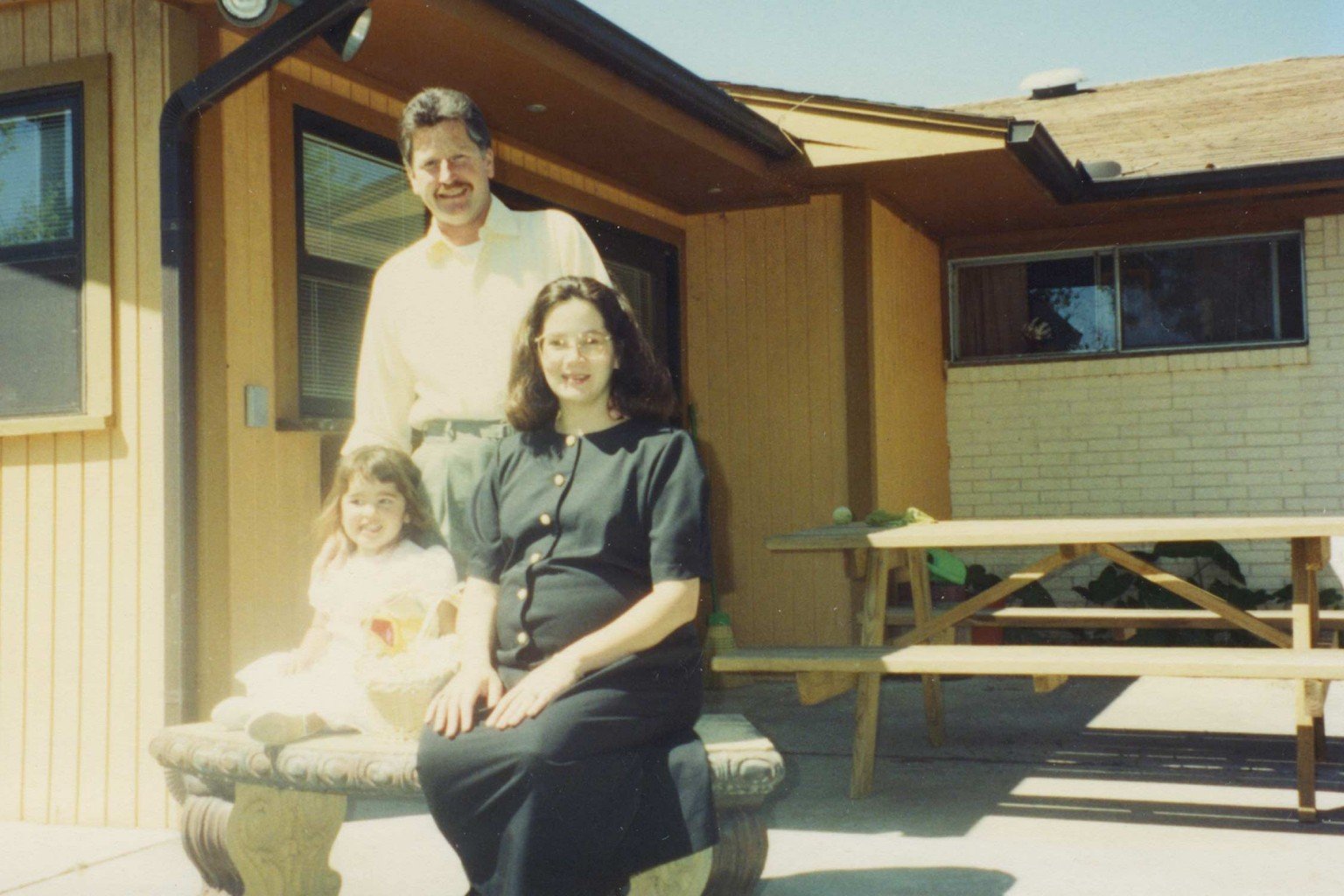

My mother was the youngest of three and the only girl. Like many Tejano kids, she spoke both English and Spanish, even at home. She met my father when he was working as a welder in Bay City, the Gulf town where she had lived all her life. They married and started a family there, and Grandma Lucy was the default babysitter. My earliest memories include the sensation of my thighs sticking to the sun-heated plastic swing hanging from Lucy’s enormous pecan tree, the heady perfume of gardenias thick in the summer air, neighbors stopping by with cigarettes for my grandmother and raspas de coco for me, and always—always—a heaping pile of pinto beans soaking in water on the counter or slowly cooking on the stove.

I grew up hearing Spanish but never really speaking it. Lucy would speak to my mother in Spanish and Lorraine would respond in English, or vice versa, or English phrases would be interspersed in Spanish sentences. It’s not something I realized I had missed or lost until later, in college: I was eager, after spending my middle and high school years with mostly white classmates, to connect with other Latinos and Chicanos. I went to an event put on by the student cultural center. Most of the attendees were majoring in Spanish or Latin American studies, all were fluently bilingual, and each seemed to have a firm grasp of their identity. I couldn’t speak Spanish well enough. I didn’t feel like I belonged, and I never went back.

Before my senior year of college, I took a summer abroad in Cuernavaca, Mexico. When I returned, feeling more sure of my Spanish than ever, I called Grandma Lucy, managing a full—if basic—conversation with her. She was so proud: “Me encanta escucharte hablar Español,” she said, and though it wasn’t the first time my grandmother had spoken to me in Spanish, understanding her completely was a new sensation. “It’s so important that you know because it’s half of who you are.”

And then I would try to speak to my mother in Spanish, she who still called me “mijita,” who was responsible for the string of Spanish curses I’d spout off while driving. I would never get very far. For one thing, Lorraine wasn’t patient enough to haggle through a conversation with my limited vocabulary. But mostly, she didn’t feel that her Spanish was “proper.” She couldn’t confidently correct me because she hadn’t learned Spanish in school and wasn’t fluent herself, and if I was going to speak the language, she said, I should speak it the right way.

My Spanish has come and gone since Cuernavaca. My ability to speak it well resurges from time to time, and some days I am confident and can recall the right words. Other days, my tongue trips over itself and my ears get confused. A few months ago, while gorging on tacos throughout the city for our taco issue, I made a point of ordering in Spanish at every taqueria. About half the time, when I tried to ask a question about the menu or about the owner, my limited language skills gave me away and the taquero switched to English. Each time it happened, I felt a twinge of shame—the same kind I imagine my mother felt every time her Spanish failed.

When we moved to Wisconsin in 1996, Lorraine would request care packages from Grandma Lucy: Pounds of tortillas from H-E-B, homemade salsa and hot sauce, Lucy’s bean-potato tacos (she’d flatten them and pack them in foil and plastic bags) and, of course, chiltepin. Chiltepin are pea-sized chiles that are candy apple-red when ripe and dangerously hot. They’re native to Texas and difficult to find in the Midwest, particularly in rural Wisconsin.

It was a family joke then, the way Lorraine would carry a stash of these peppers in her purse, wrapped in a paper towel and tucked into an inside pocket. Every few weekends, we’d drive the fifty miles to the nearest shopping mall and Walmart. We’d have lunch at Friday’s. She’d order a burger and ask for jalapeños—and then when the burger came, she’d pluck two or three chiltepin from her cache and add them, too.

My mother was not adventurous in the kitchen, but she had a handful of recipes that she relied on throughout the week. One, and a family favorite, was her Mexican rice. It’s simple enough: long-grain rice, tomato sauce, Rotel, onion, spices and chiltepin (if she had it—if not, fresh serrano). The aroma that permeates the kitchen as it simmers for half an hour is powerful and immersive, garlic and tomatoes and herbs blossoming together. It was always accompanied by the sound of my mother’s soft, off-key harmonizing with either Van Morrison or Luis Miguel.

Lorraine never wrote down the recipe, but I helped her make it countless times. Still, I could never successfully recreate this dish, even when I would call her to guide me through it.

After a brief battle with leukemia, my mother died in 2014, just ten days after her fifty-fifth birthday. In December 2020, after months of languishing under a cloud of pandemic-born ennui, I made my annual holiday visit back to the family farm in Wisconsin and decided, since I was working remotely, to stick around for a few weeks past the New Year. Weeks turned into months. Like many, I found myself spending more time in the kitchen—in my mother’s kitchen, using her appliances, her cutting board, the glassware she had purchased at that estate sale that one time. I read the memos she had scribbled in cookbook margins in her chaotic cursive. There was something buoying about standing where she stood.

One evening, as Moondance played from the kitchen Alexa, I lined up the ingredients for her Mexican rice. I browned the rice first (my mother had always used bacon fat, kept in a jar next to the stove, but I swapped it for olive oil to appease my vegan sister who was also farm-bound during quarantine). I measured water not with cups but with empty aluminum cans. When it was done, I spooned the fluffy, ruby-red rice into a flour tortilla with refried beans, a slice of American cheese and slices of fresh serrano. It was perfect.

Even without perfect Spanish, I have always found belonging in Mexican flavors. That part I have never questioned. Ajo, comino, tomatillo, cebolla, cilantro, arroz y frijoles—I know this food in my bones. The aroma of my mother’s rice is itself a kind of home.

Experiences, not bloodline percentages, shape our identities, and my most formative experiences are rooted in Latin culture. I love my father and I am not denying his influence or heritage, but it was never as present or powerful: I didn’t grow up eating corned beef or speaking Gaelic.

Recently, I asked my siblings what race or ethnicity box they check when they’re filling out forms. My sister, Valerie, was five when we moved from my mother’s hometown, and my brother, Patrick, was just two. Valerie prefers not to disclose. Patrick makes a random selection. Both, if pressed, would say white. My Uncle Mingo—an Air Force veteran and drummer who played in garage, country western, Tejano and blues bands and imbued his little sister with impeccable taste in music—adamantly calls himself American.

What’s in a name, anyway? A surname may offer clues about a person’s lineage, but it’s not a rule. I am a fourth-generation Tejana. For me, incorporating my mother’s name is an affirmation. I am holding space for my dual heritage. I am honoring my mother and my grandmother. I am giving that confused young girl the name she has carried in her heart all this time.

My sister spooned a pile of the Mexican rice I made into a bowl and grabbed a tortilla. Valerie is rarely impressed, so when she helped herself to seconds, I asked her what she thought.

“This is just like mom’s,” she said. “How did you do it?”

I recounted the steps, but it wasn’t just the recipe or the timing. I found something my mother had left for me, some generational secret that uncurled in my belly like heat from a chiltepin.

Lorraine’s Mexican Rice

YIELD | 6 servings

PREP | About 5-10 min.

TOTAL TIME | About 30-40 min.

2 tbsp. bacon grease (For a vegan option, olive oil is fine. My mother kept a jar of bacon fat next to the stove and used it instead of oil for pretty much everything.)

2 cups long-grain rice, uncooked

1 white or yellow onion, diced

2–6 chiltepin peppers (diced serranos or jalapeños are fine, too)

2–6 cloves garlic, minced (more is more when it comes to garlic and spice, but you do you)

2 16-oz. cans tomato sauce

1 10-oz. can Rotel (medium or hot)

2 cups water

1/2 bundle fresh cilantro, chopped

1/2 tbsp. garlic salt, or to taste (regular salt is fine, but then add garlic powder)

1/2 tbsp. cumin, or to taste

1/2 tbsp. cayenne, or to taste

1/2 tbsp. black pepper, or to taste

1 lb. protein of choice (shrimp, chorizo sausage, rotisserie chicken, etc.), optional

STEP 1

Heat a large, five-quart nonstick pan on medium. Add bacon grease or olive oil, let warm (about 1-2 min.), then add rice, onion, peppers and garlic. Stir ingredients in pan constantly with a spatula until rice is turning golden. Be careful not to burn it. This step should take about 3-6 min.

STEP 2

Add tomato sauce, Rotel and water. Instead of measuring the water in cups, my mother always poured water directly into the empty tomato sauce can—it was about the same measurement and had the added benefit of getting every bit of tomato sauce out.

STEP 3

Add cilantro and dry seasonings. I never measure the seasonings and I tend to be very liberal. Use your best judgment. This recipe is vegan if you use oil instead of bacon fat, but if you want to make it a one-pot meal, add rotisserie chicken, chorizo or shrimp at this stage.

STEP 4

Stir mixture and bring to a rolling boil, then lower heat to a simmer and cover pan with lid. Let simmer for 20 minutes or until rice is tender and cooked through. Remove from heat and serve with refried beans and margaritas.