It’s been a century since a pandemic brought the nation to an unsteady stop. After such a passage of time, there’s only the faintest public memory of the deadliest disease outbreak humanity has ever seen, one that claimed fifty million lives worldwide.

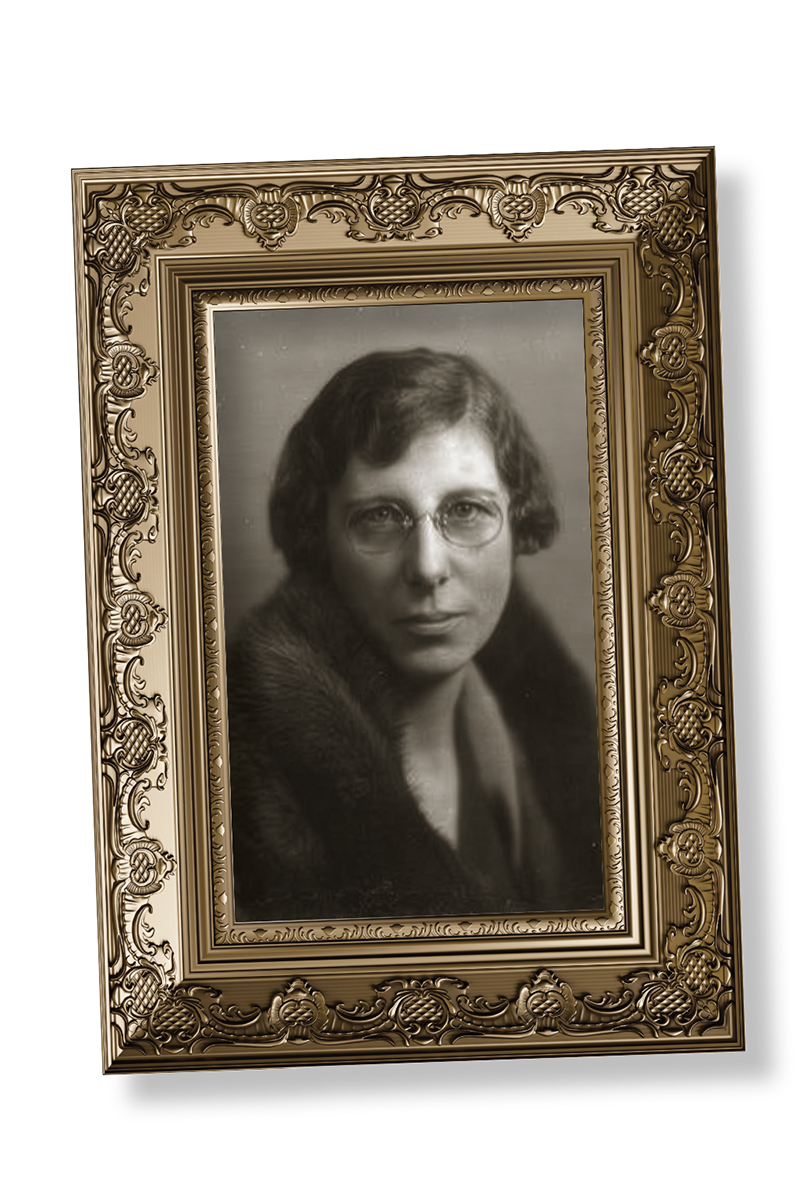

That’s why Nancy Tomes is suddenly getting calls from across the country. Tomes, a professor of history at Stony Brook University on Long Island, is lauded as one of the world’s most knowledgeable scholars of the pandemic in which a third of the world’s population fell ill. “It’s a very weird sensation to be in this smallish clan of historians who have studied the Spanish flu in depth,” she says. “We’re all dumbfounded to think that all this old stuff that I’ve read and studied still comes in handy.”

Part of Tomes’ knowledge comes from a project for which she joined with a team of historians, epidemiologists and virologists to do a comprehensive cross-disciplinary study of the Spanish flu pandemic on behalf of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Department of Defense.

When she first heard about the novel coronavirus that emerged in a wet animal market in the central Chinese city of Wuhan, she started to worry.

Then, like a lot of us, she stopped worrying so much for a few months.

“There’s been this sense that the big one was coming—we just didn’t know which one it was going to be,” she says. “Finally, it’s here. And I’ll be the first to admit that when the first word of it came out, I thought to myself, ‘Whoa, this is creepy,’ but then there was sort of this period when it was kind of like, ‘Well, this isn’t so bad.’ I think we were lulled into a false sense of security that it couldn’t possibly be as bad as the 1918-1919 pandemic or, God help us, the bubonic plague. But, dang, it’s turning out to be pretty bad.”

We spoke to Tomes about how this pandemic compares to the one a century ago. Her answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you start studying the Spanish flu?

I got interested in why ordinary people came to believe in the existence of germs. With the germ theory of disease, there’s a before and an after. That was not the common way of explaining what we call infectious diseases in the 1830s or 1840s, and there’s this shift that takes place.

It begins with scientists experimenting and saying, “I think what passes from one person with smallpox to another person with smallpox is not just some inert thing; it’s alive, and it’s a microbe.” Louis Pasteur has this concept that germs are like a ferment in yeast. That was around 1857, and then there’s a lot of arguing about it for about twenty years.

But by the mid-1870s there’s a really conclusive body of laboratory experiments. This guy, Robert Koch in Germany, does this brilliant series of steps where he can show you the bacteria that causes cholera under a microscope. Cholera doesn’t just pop out of the air or the water or whatever, which was the miasma theory. It’s a very specific bacteria that lives in people and goes out in your feces and into the water.

Basically, I was studying how those ideas got out to the general public and how people changed the way they behaved to keep from getting these terrible diseases. I wrote a book about it called The Gospel of Germs, and it’s all about how everyday life changed when people started believing in germs.

When I go back and look at that book, I’m struck by the fact that I kind of threw in the Spanish flu pandemic at the end because so much happened before it. But because I had written about the popular understandings of germs, when the CDC and the Department of Defense wanted to do a comprehensive look back at the Spanish flu, I was part of the team. And that’s when I did all that research. I went back and I was like, “Whoa, I should have spent more time looking at this.” But it was already a long book.

What similarities do you see between the Spanish flu pandemic and what happening right now?

I went back and I looked at what we now call social distancing. All of the rules that we’re now following were things people were being taught—not coughing and spitting in what they called “a careless fashion.” All those things were called upon during the pandemic to try to slow the transmission of that very deadly strain of influenza.

I was also interested in this as a moment of American life where the interdependence that we are now so familiar with was just coming into focus. The ideas that if you shut down the city, people were going to starve, or that you take public transportation to work [were new]. By then, people were even used to going out for entertainment, whether it was vaudeville or movies. This was the moment people realized there was something—the old fashioned term for it was mass society—but it’s basically just a whole lot of people connected to each other through work or play. That made it really difficult to shut down this fast-moving infection.

If you go back and read these public health accounts of what they tried to do to slow the Spanish flu down, it really is like reading what’s in the papers today. Very similar tactics and very similar concerns.

This question is probably more philosophical because I don’t think there’s a real answer, but was it easier or harder to shut down a city in 1918 as opposed to today? It seems to me that the vast majority of Americans really could not leave their house right now, but they also have different expectations about life.

It’s something I’ve been thinking a lot about. In some ways, I’d say it’s easier for us now—but I draw a big asterisk on that and say it’s easy for those of us who own our home and have secure incomes. What we’re seeing in cities like New York is that this pandemic is showing the number of people who don’t have somewhere secure to live. Historians will tell you that pandemics always show you the vulnerable parts of your society—it’s like a heat-seeking missile. You can say coronavirus will affect the rich as well as the poor, but it’s always going to hit poor people harder.

But if we limit it to relatively comfortable people, it’s easier because one thing that I’m looking at right now is a large refrigerator. Back then, even wealthy homes still had ice boxes—they didn’t have freezers. So the struggle to get fresh food was more of a problem. We can sit here and turn on Netflix. My daughter and my husband and I are watching Tiger King. Wow, what a crazy show. Back in the day, if you were stuck at home, I guess you could play the piano and sing songs, but our ability to entertain ourselves or even talk to each other was very limited.

What did regular people in 1918 have going for them that we don’t have today?

I think they were better prepared to deal with the lack of order and the unpredictability of this. This was a generation that had bad infectious diseases all the time, and there were no antibiotics. They were better at understanding that Mother Nature is a force to be reckoned with and didn’t think we should be able to snap a finger and have a cure for the virus or even a vaccine. I think we’ve been schooled to expect that medical science can perform miracles.

One of the things that really surprised me in reading about the 1918 flu epidemic was that when modern scientists finally found a way to identify the virus from frozen bodies in the Norwegian Arctic, they found out that it was just H1N1—it’s the most common, vanilla cause of influenza today. It’s just not as deadly because we’ve built up immunity.

H1N1 is now plain vanilla, yeah. And you could say the same thing about the coronavirus. It’s in the same family as the common cold. This is one reason I try not to get hyper-judgmental about the way people are reacting—because of what we didn’t know in the beginning. There are other ways that I’m hoping we come out of this, including taking the planning piece of it more seriously. That’s my hopeful scenario: that this will be the wake-up call that we needed. Some of what I’ve read has suggested that the countries that got hit really hard by SARS—South Korea being one of them—did better this time around because they knew better what to expect. Whereas with the United States, it was kind of like, “Yeah, it’s not going to be a big deal. It’s a Chinese virus. We’re

not Chinese.”

Did you hear about this virus in January, and what was your immediate reaction?

Yeah, I was on top of it in January—but I freely admit I’m weird in the sense that that’s kind of the stuff that I listen for. So my little ears perked up right away: “Uh-oh. Wet markets. Wuhan.” I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been invited to give a talk where, for example, I’m supposed to put Ebola in historical perspective and Zika popped up before I could give the talk. So I was already attuned to the problem of emerging diseases. I was primed to see this as a possible nightmare. But again, it’s kind of my line of work to expect that kind of thing to come along.

You’re not a scientist, but as you’ve studied pandemics, I want you to play Monday Morning Quarterback here. Hop back to the beginning. If you’re leading the country, what do you do differently? Do you shut the border, Madam President?

OK, I’ll be armchair quarterback. My understanding is that there has been a plan agreed upon by whoever does these things—the CDC and others. We had a plan. So Madam President would have said, “I want that plan.” My understanding is that in that plan, there are messages to immediately up the amount of protective gear. If we had placed those orders in late January, we wouldn’t be sitting here in the mess we are now. There is stuff in that plan about testing—you know, making sure you get quick testing and you make it freely available to everyone. To me, the fatal lack of preparedness was the inability of anybody to get test kits—reliable test kits.

You’re a historian who has studied how regular people change their behavior as a result of these pandemics, so I have to ask: Do you think Americans are going to start wearing masks when they’re sick now?

My guess is that, from now until the people who are old enough to remember this die, most American homes are going to have an N95 mask or something comparable on hand. That this is going to remain as such a trauma in our collective memories that having a mask on hand—and probably also a case of toilet paper—may in fact become the new normal.