Striking up a conversation with any KC bar connoisseur is certain to lead to a list of dark and moody bars reminiscent of a time long gone. Nostalgically referred to as speakeasies, the modern versions of clandestine Prohibition-era bars are experiencing a surge in popularity that just so happens to coincide with the 104th anniversary of Prohibition.

It’s easy to simply accept speakeasies—a name that came about when patrons needed to “speak easy,” or quietly, about places selling illegal booze—as yet another modern-day “retro” trend. However, here in KC, these ventures spring from a rich, complicated past that’s intertwined with the city’s infamous history of corruption.

In 1920, just as the Constitution’s 18th Amendment was adopted prohibiting the manufacture, sale and transportation of intoxicating liquors in the United States, Kansas City was in the midst of entering a political era known as the Pendergast Years.

Tom Pendergast, considered one of the country’s most corrupt political bosses, was an unelected city dealmaker and leader of the Goat faction of the local Democratic Party, referencing the many goats the city’s Irish population housed in their backyards. Under Pendergast’s reign, from 1925 to 1939, KC was known as “the only major city in the country that largely ignored national Prohibition laws,” says Ryan Maybee, career bartender and founder of J. Rieger & Co. Distillery and the Hey! Hey! Club.

Chuck Haddix, a jazz historian and the curator of UMKC’s Marr Sound Archives, says Pendergast was “never elected to any office […] He delivered votes for the machines, and since he controlled city hall, he was able to foster graft and corruption in Kansas City.” The city’s perceived lawlessness garnered it the title “Paris of the Plains” and, more darkly, the “Crime Capital of the Country.”

Speakeasies and Pendergast

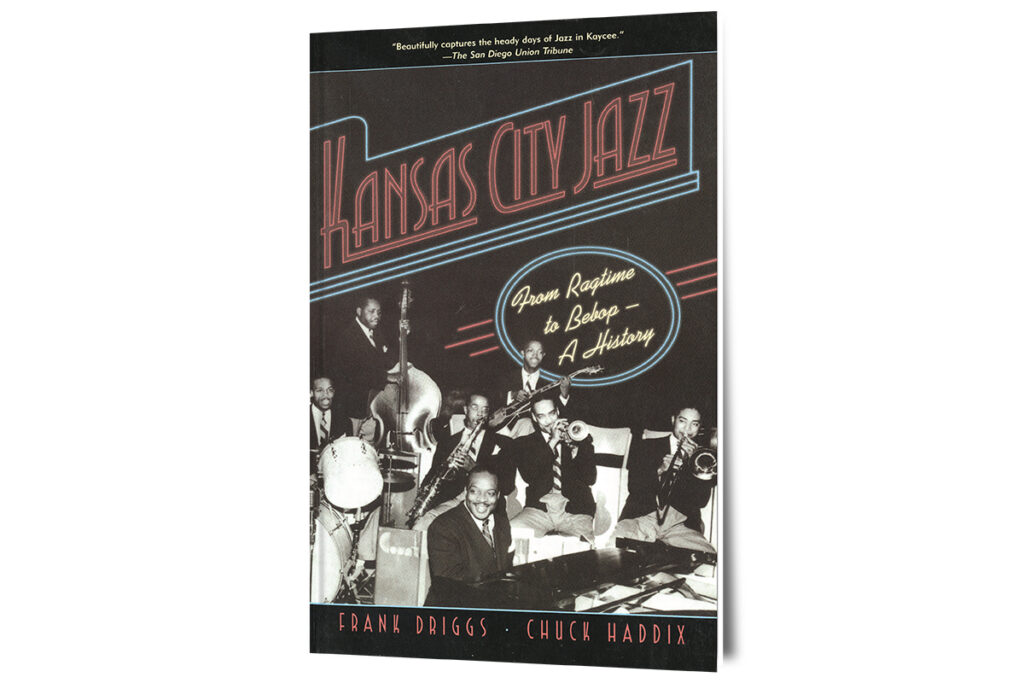

In the book, Kansas City Jazz: From Ragtime to Bebop, co-authored by Haddix and the late Frank Driggs, the authors muse that Prohibition in Kansas City was a part of the city’s ongoing “tradition of vice and lawlessness,” stemming from the city’s roots as a frontier town. Under the Pendergast machine, Kansas City’s nightclubs, prostitution, gambling and alcohol sales flourished. All these and more were housed within the city’s dozens of ‘speaks,’ or speakeasies.

Maybee defines the Prohibition speakeasy as, “simply put, a place you could drink during Prohibition when it was illegal. [Speakeasy] referenced either ‘careful who you tell about it,’ or, a lot of times you would want to keep the noise level down to keep from being caught.” However, in the Pendergast years, getting caught was the last thing on most proprietors’ minds. “Kansas City was the only major city that did not have a single felony arrest for the sale of alcohol during Prohibition,” Maybee says. This was largely due to “Boss” Tom Pendergast.

As the head of the Jackson County Democratic Club, Pendergast controlled city hall with ease, with cronies judge Henry McElroy and police chief Otto Higgins under his thumb. Through his influence and power, both financially and through relationships he’d fostered with illegal sellers of spirits, Pendergast encouraged city officials to look the other way when it came to nightclubs, liquor sales, prostitution and gambling.

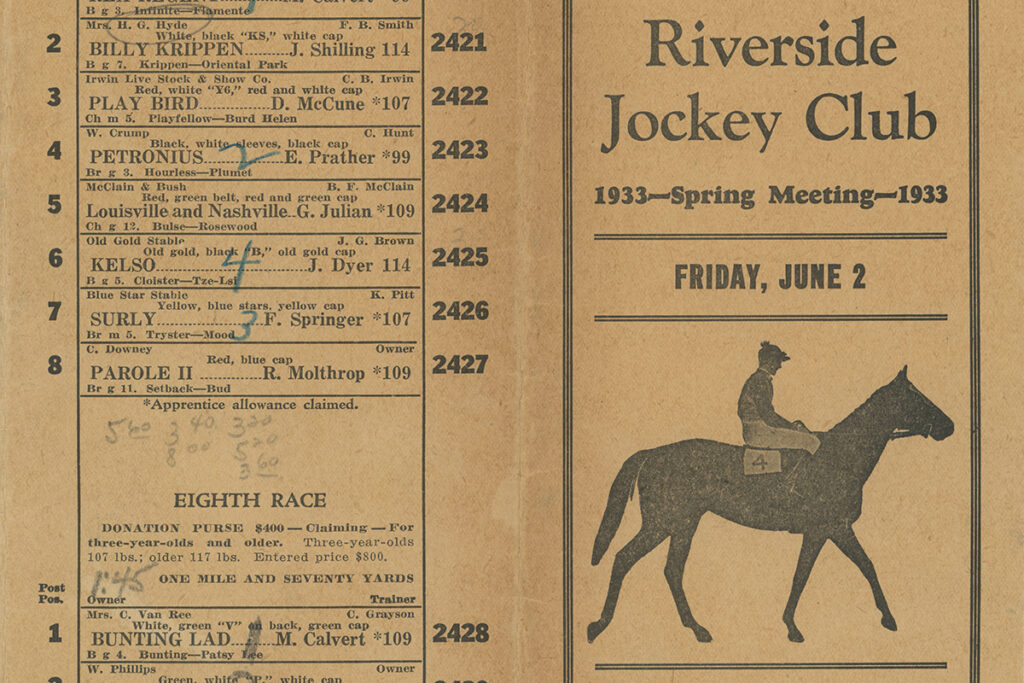

Pendergast didn’t just open the market for proprietors of all things vice; he himself was in the business of illegal gambling and liquor sales. During Prohibition, the Pendergast machine opened the Riverside Park Jockey Club as an illegal race track. There were an estimated 50 bars promoting live music and spirits between 12th and 18th streets alone, and brothels such as Annie Chambers’ aristocratic brothel were operated with women positioned in well-lit street-facing windows, openly procuring customers. In reference to the city’s civic sanctioning of prostitution, Higgins, the police chief at the time, is quoted by Haddix as saying: “If you bother the girls, you just push them into the back room. Then you don’t know what’s going on. This way we can maintain control over them.”

Worst-Kept Secret

In similar laissez-faire fashion, nightclubs and dance halls lined the streets with little concealment. In an article remembering the legacy of speakeasy proprietor Milton Morris, Haddix writes: “As part of the christening [of nightclubs], it was considered good luck to give a cab driver the key to the club and five bucks with instructions to drive as far as he could and throw away the key. The doors [to the clubs] never closed.”

Morris was one of many who began his career in liquor during Prohibition. In 1929, at just 18 years old, Morris opened his first bootlegging business, Rendezvous, which was a drugstore on 26th Street and Troost known to sell alcohol under the guise of using it for medicinal purposes. In 1931, Morris opened his infamous speakeasy, Hey Hay Club, on Fourth and Cherry streets in a converted barn where patrons sat on bales of hay, hence the club’s name.

Like its fellow speakeasies, Hey Hay did not conceal itself as a den for liquor and marijuana, boasting 25 cent whiskey shots and marijuana joints on a cardboard sign in plain view. As Morris noted, since both were illegal, why not? Morris, who went on to become a legend in the Kansas City bar scene, was known as a great storyteller of his Prohibition days, often blurring the lines of truth and fiction and always telling the tales while smoking his trademark cigar. Morris’s club quickly became entangled in the jazz scene, which was flourishing with the rising opportunities for musicians to entertain at speakeasies. Jazz leviathans like Count Basie, Jo Jones, Lester Young and Ben Webster were regular performers at Hey Hay.

Kansas City’s lack of discretion during Prohibition meant the city held tremendous influence on the development of jazz at this time, with the plethora of clubs creating jobs for musicians across the Southwestern territories. “Musicians from across the country flocked to Kansas City, drawn by the easy ambience and plentiful jobs in the dance halls and nightclubs sprinkled liberally between 12th and 18th streets,” Haddix and Driggs write.

The influence of jazz bands can still be seen in KC bar culture today, with Hotel Kansas City’s speakeasy, Nighthawk, paying homage to the Coon-Sanders Original Nighthawk Orchestra, which recorded and performed throughout Kansas City during the Pendergast Years. The historic 18th and Vine District, often referred to as Kansas City’s other downtown, is regularly credited as the birthplace for the distinctive Kansas City jazz style. Andy Kirk of Twelve Clouds of Joy—a jazz band that often played in the area—described the historically Black neighborhood as “a regular Mecca for young Blacks from other parts of the country aspiring to higher things than janitor or chauffeur.” Jazz musicians at that time were regular patrons of the speakeasies, frequenting the Sunset Club (located on the southwest corner of 12th and Woodland), the Reno Club (just east of City Hall), Hey Hay and the red-light district running south on 14th Street.

In contrast to KC’s thriving underground bar scene, distilleries had more difficulty surviving under national Prohibition laws. Leading up to prohibition, J. Rieger & Co. Distillery—first established in 1887 by Jacob Rieger—was not just a Kansas City brand but a national brand built on shipping spirits across the country. “Bars and nightclubs continuing to operate during Prohibition is one thing, but if you were an actual manufacturer, that would have been a far more challenging thing,” Maybee says.

In 1920, Jacob’s son Alexander Rieger, who by then had taken over the business, transitioned into banking because, as Maybee says, “[J. Rieger & Co.] was just too big.” With distilleries shut down, bootlegging became a lucrative business for everyone from citizens to law enforcement themselves. In a letter to the Kansas City Star in December of 1928, Rev. O. W. Stanbourgh wrote, “One of the first things I learned about the community was that a bootlegging joint was being operated upstairs over 616 East Thirteenth Street.” The reverend alleged to the Star in his letter that he saw “police officers in uniform frequent the place” and “motorcycle patrolmen would frequently leave their mounts […] and remain for half an hour and sometimes even several hours.”

Although the city’s relationship with speakeasies and bootlegging remained largely unchallenged, the repeal of Prohibition in December of 1933 forced the major players in speakeasies, bootlegging, gambling and prostitution to navigate their entrepreneurship in new ways.

Morris went on to open several other bars, including the original The Ship downtown on East 10th Street and his namesake, Milton’s Tap Room, where he was regularly found posted by the door swapping stories with regulars.

Today’s Speakeasies

In 2014, Alexander Rieger’s great-great-great grandson and only living relative, Andy Rieger, along with career restaurateur Maybee, relaunched J. Rieger & Co. Distillery, making it Kansas City’s first distillery since the Prohibition era. Shortly after, Tom’s Town Distilling Co. opened in January of 2016, with its name and menu paying homage to Tom Pendergast and the Prohibition era.

Now, 104 years after Prohibition was first enacted, conversations with KC bartenders and avid cocktail enthusiasts alike are still almost certain to lead to a list of today’s best speakeasies. But what makes these modern bars “speakeasies,” and what exactly has brought the term back into use? Maybee has an answer. “The modern day speakeasy started roughly in 2000, with a place in New York City called Milk & Honey,” he says. “[Owner] Sasha Petraske tried to recreate that spot of going into a speakeasy during Prohibition, which required discretion and sense of doing something wrong.” Maybee goes on to describe this atmosphere of rule breaking as a “powerful experience that was quite a bit different than the loud, bright, bustling nightlife we were used to.”

From there, the modern speakeasy became a trend that spread throughout the country’s community of bar owners, bartenders and booze connoisseurs, with legendary modern speakeasies such as The Violet Hour in Chicago’s Wicker Park neighborhood and The Franklin Mortgage & Investment Company in Philadelphia following soon after.

“Other entrepreneurs and bar owners started to mimic that concept, and I was one of them,” says Maybee, referencing his bar, Manifesto, which operated in the basement of J. Rieger & Co.’s distillery for 12 years before closing during the pandemic in 2020. Manifesto, one of Kansas City’s earliest contemporary speakeasies, is still legendary. Local career bartender Nate Weber recalls entering the intimate bar lit exclusively by tea lights through a back door after heading down a long alley.

Manifesto is now remembered in Maybee’s latest speakeasy, the Hey! Hey! Club, paying homage to Milton’s Hey Hay Club. “Hey! Hey! is kind of Manifesto’s second act,” Maybee says. J. Rieger & Co.’s Hey! Hey! Club, now located at 2700 Guinotte Ave., can be entered from the ground floor of the distillery, where visitors are greeted by intimate velvet and leather accents, wingback chairs and a functional fireplace.

Another speakeasy you’re bound to hear praised is the elusive Swordfish Tom’s—elusive mainly because of its popularity. It’s located discreetly in the basement of an unmarked building at the eastern end of West 19th Terrace, and upon entering the bar’s unmarked alleyway door, you descend a staircase in hopes you’ll find a green light outside the bar’s door, indicating there’s space for new customers to enter. If you’re lucky, after finding the light green, you’ll knock to be let into the underground speakeasy’s red-brick room, with a massive wrought iron heater taking up the majority of the right side of the hall and the bar’s modest four-stool bar in the back left corner. Customers lounge closely with one another in plush seats and along couches, sipping cocktails from a seasonally rotating menu.

Further downtown, there’s the regal Hotel Phillips. Slipping down a side entrance behind the hotel’s front desk leads you into a truly secretive speakeasy, P.S. Speakeasy. At P.S.—in old Prohibition fashion—you’re likely to find jazz bands playing loudly in a basement adorned with private booths, where well-dressed customers sit while discreet bar staff carefully serve cocktails in thin, delicate glassware.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is the Mutual Musicians Foundation, more commonly known as the Foundation, located in historic 18th & Vine. Famously known by KC’s service industry workers as the “last stop of the night,” the Foundation is a jazz club built inside an old house with a bar equivalent to one you may find at any regular house party. Upstairs, jazz bands play melodic rhythms well into the early hours of the morning. Outside, attendees share cigarettes on the backyard-style patio. A club well aware of its historic roots, the Foundation is maybe as close to living in Prohibition as you can get today.

With Prohibition-inspired bars now opening regularly throughout Kansas City—most recently, Voo Lounge opened in February 2023—it makes you wonder what exactly it is about speakeasies that still draws crowds. Maybee credits the draw of speakeasies to a need felt by almost every hardworking resident: the need for escapism. “People are looking for an experience and an escape,” he says. “Going out is an escape. You want to escape the day-to-day ritual of your life.”