For the last decade, voters in Michigan have overwhelmingly voted for state representatives from a political party founded in Baltimore. But that party has not once held power. Rather, a political party founded in Wisconsin has held supermajorities, despite receiving fewer votes in every election over the last decade.

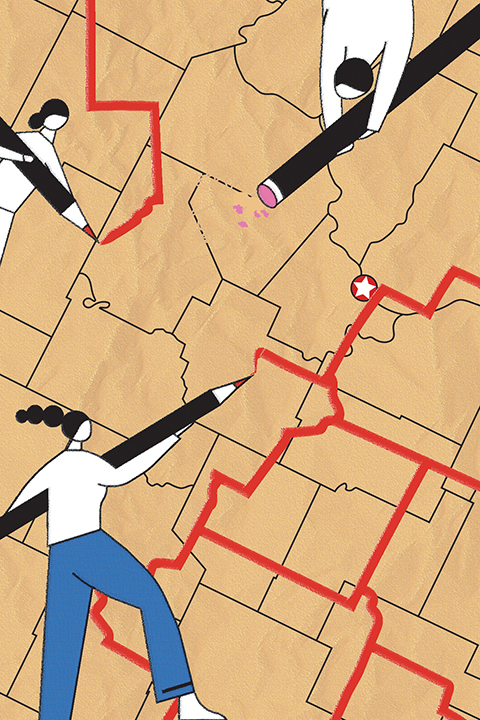

How can one party dominate the Mitten State’s politics despite having fewer voters? It’s all because of a marriage between the ancient art of gerrymandering and the power of modern big data, says David Daley, author of Unrigged: How Americans Battled Back To Save Democracy, and Ratf**ked: Why Your Vote Doesn’t Count.

It’s going to get worse with the upcoming once-a-decade redistricting process—especially in Missouri.

In 2018, Missouri voters overwhelmingly passed an amendment to the state constitution to take redistricting out of the hands of party operatives. But in 2020, the same voters narrowly overturned it through the confusingly worded Measure 3.

“Missouri voters said we want to do something about this, we want to clean this up, and sixty-two percent of them signed on for reform in 2018,” Daley says. “The trouble is, as you saw in Missouri, that people can go to these superhuman efforts and become heroes of democracy only to have their legislatures undermine them, just like that.”

We talked to Daley about the somewhat bleak future of pro-democracy reforms.

“All of the structural flaws have been laid bare and weaponized in service of an enduring minority rule that is going to be very difficult to dislodge,” he says.

Big data changed everything. “We have had gerrymandering as long as we’ve had politicians,” Daley says. “Patrick Henry tried to draw James Madison out of the very first Congress.”

But in the same way that analytics revolutionized baseball, things have changed in the digital age. Maptitude—the software that political operatives use to draw the lines—was a game changer: “In 2010, you see this quantum leap in the sophistication of the software, the speed and power of the computers, and the granularity of the data.”

Public data allowed operatives to draw districts based on party, turnout, home value and gun ownership. Then, add data gathered by Facebook.

“When you combine all of that, you’re able to draw the lines where you know the impact of moving one of those lines one block in any direction,” Daley says.

Political scientists were slow to understand modern gerrymandering. The lines drawn using big data have proven shockingly powerful.

“The political scientists used to think, ‘oh, gerrymandering gets you a temporary advantage,’” Daley says. “But the technology that is used to draw these maps, the data that goes into picking these voters and putting them into districts, and our polarization in general are all so intense that the maps that were drawn last decade held up for ten years.”

Polarization is driven by gerrymandering. Have a problem with Rep. Rashida Tlaib, D-Mich? Don’t like Rep. Jim Jordan, R-Ohio?

Either way, blame gerrymandering. Both representatives come from oddly shaped, heavily gerrymandered districts that lump partisan voters together, incentivizing politics that plays to the extremes of their respective party bases.

“Opinion polls show that there is a path forward in this country on just above every hot-button issue,” Daley says. “The structure of the system has prevented us from even having votes on some of these issues where we could have progress.”