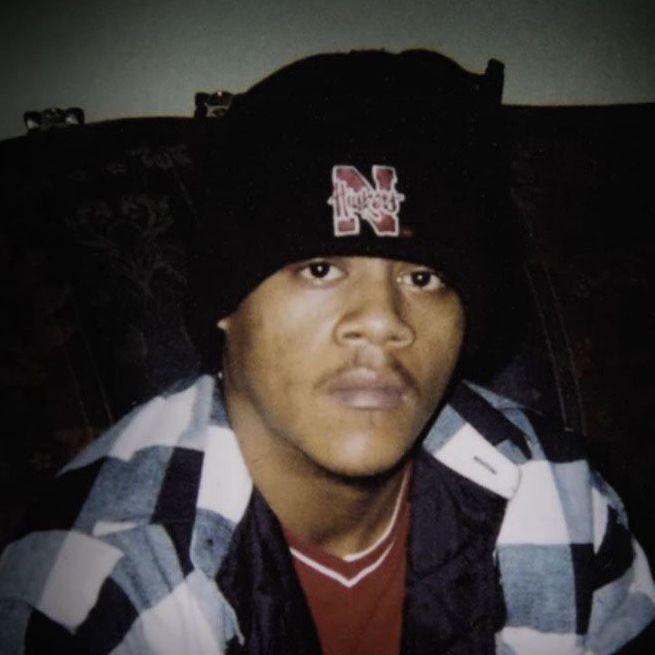

It catches your eye the minute you walk in: a portrait of him from his brother’s wedding. You may have seen it on Netflix or Facebook pages, but seeing it in person is somehow different. It’s perched next to the large TV in Maria Ramirez’s house in Topeka. The TV dwarfs the photo of Alonzo Brooks in size, but the photo still holds your attention.

He’s faintly smiling, dressed in a tux. A crisp white shirt and bow tie and a ring perched on his right hand all preserved in a slightly grainy picture bring you back to the time before everything changed for the Brooks family. Alonzo Brooks mysteriously disappeared in April of 2004 from a party in the tiny Kansas town of La Cygne. His body turned up a month later in a creek right behind the house where he disappeared, offering other puzzling details. The case has been cold since 2004, but a recently released episode on the Netflix reboot of Unsolved Mysteries has renewed interest. The FBI reopened the case, offering a hundred-thousand-dollar reward and exhuming Alonzo’s body for a new autopsy in July.

“A lot of families’ cases never get solved,” says Felica Brooks, one of Alonzo’s older sisters. “And some people give up. We’re not giving up.”

Where are you going tonight?”

That’s one of the last things Maria Ramirez remembers asking her son before he left their Gardner, Kansas, home.

“He wasn’t the type of person to just go to parties with a lot of people,” she says. “Even at family gatherings, he would keep to himself. That’s why we were surprised, to begin with, that he wanted to go to the party that night.”

The house party in La Cygne attracted young people from many small towns in the area, including Paola, Spring Hill and Olathe. The majority of partygoers were from Gardner and were people Alonzo was familiar with, according to Josh Pratt, a filmmaker who has been researching the story for over six years. Alonzo and his friends Justin Sprague, Daniel Fune and Tyler Broughard were some of those in attendance. Fune and Broughard arrived at the party separately, but Sprague took Alonzo and was supposed to be his ride home. (None of Alonzo’s friends could be reached for comment by Kansas City magazine.)

The white gothic farmhouse built in 1880 where the party was held was, and still is, a rental property owned by Bradley and Janell Aust, residents of La Cygne. At the time it was rented to a twenty-something man from Gardner. It is situated just off the main road and surrounded by open fields teeming with soybeans. A barbed wire fence surrounds the back of the house while a creek lies a football field’s length away—Alonzo’s body was found in that creek a month after his disappearance.

You can imagine the backyard bathed in light from the house, music filling the air and the faint illuminations of the downtown area lighting up the night sky as nearly a hundred young people dance, drink and have a good time. Alonzo Brooks, who was half-Mexican, half-Black, was reportedly one of three people of color at the party.

Some witnesses told authorities he was harassed because of his race. Some of those at the party include members of the Boone family—longtime La Cygne elites. The names Pat, Jerry and Tiffany Boone often pop up online, with accounts saying they came into conflict with Alonzo Brooks at the party. (Kansas City reached out to the Boones without reply.) Their second cousin, Mandy Jenkins, who was eleven at the time, says of the Boones: “People love and people hate them.”

As the night went on, Sprague, who drove “Zo” to the party, left to get cigarettes, leaving Alonzo at the party with promises he would return or help his friend find a ride home. Sprague never returned. He told law enforcement that he got lost on gravel roads. That left Alonzo, who never learned to drive, with no ride home. The next morning, he was missing, with only his shoes and hat found at the site of the party. “I knew something was wrong when I saw that he never came home,” Alonzo Brooks’ mother, Maria Ramirez, says.

She remembers peeking into his room in the morning only to see Alonzo’s bed undisturbed. Her heart sank. She filed a police report that morning. She gathered with family and waited, holding their breath for answers that would never come.

The Linn County Sheriff’s Office—Marvin Stites, who has since passed away, was the sheriff at the time—conducted searches of the area and tried to question those at the party about what happened, according to county officials. They brought in the Kansas Bureau of Investigation two days after Alonzo was declared a missing person.

“I remember searches happening and lots of police cars out there,” says the current mayor of La Cygne, Debra Wilson, “but they really limited any news or real information. Gossip was all most of us ever really knew.” A month later, neither the sheriff nor KBI had made any progress in the case. The Linn County Sheriff’s office declined to comment and refused to give Kansas City copies of public records related to the sixteen-year-old case, saying that it’s “under investigation” by another agency. “We had no idea what our options were,” Alonzo’s aunt, Angela Ramirez-Cox, says. “We just did what the authorities told us and we believed in them.”

“We tried to do it the right way,” says Demetria Brooks, another one of Alonzo’s older sisters. That’s when the Brooks family decided to take matters into their own hands. Billy Brooks Jr., Alonzo’s older brother, went to La Cygne and got permission for his family to run their own search. On May 1, 2004, they found a decayed body covered in brush on the bank of the creek, right behind the farmhouse—an area that any proper search by law enforcement would have previously covered.

According to the family, it’s not clear to authorities whether Alonzo’s body was in the creek before it was found or if it was moved there later. But his brother notes that Alonzo’s body looked well preserved—certainly not like he was out in the elements for over a month.

The bank of the creek is steep and obscured by trees and brush, but today the creek is relatively shallow and calm. There is trash scattered everywhere. Beer cans, bricks, beads and glass remind you that in the past this creek has flooded—but in 2004 it didn’t.

The family used search dogs and wore orange vests as they trudged through woods and fields. It was about an hour and twenty-five minutes into their search when they found Alonzo’s body. His brother, father and uncles all scurried down the bank to his body.

Demetria Brooks remembers photographing the scene from the edge of the bank with her sister, Esperanza Roberts. “Essie [Esperanza] fell to her knees and was like, ‘I can’t,’ and she handed me the camera,” Demetria Brooks says. “I remember leaning over the edge trying to get as much as I could. I almost fell. They had to pull me back.”

“I didn’t think we were going to find him that day,” Angela Ramirez-Cox says. “I thought we were going to leave empty-handed. Which would be worse, you know, not being able to bury him.”

An autopsy conducted at the time—standard protocol in such disappearances—was not able to conclude how Alonzo died. Foul play has been suspected, but the original autopsy done by Dr. Erik Mitchell found no signs that Alonzo had fallen or been beaten up. There was no water in his lungs to indicate drowning. His throat was too decayed to indicate whether he had been strangled.

However, there’s reason to question the rigueur of the autopsy.

Mitchell, the Douglas County coroner at the time, had relocated to Kansas after being investigated for misconduct as the chief medical examiner in upstate New York. An Associated Press article from 1993 states that Mitchell had engaged in misconduct, including harvesting organs without family permission and improperly storing skeletons in his office. Mitchell was not charged with a crime but was asked to resign. He then moved to rural Kansas, where he worked from 1996 to 2018. For their part, the Brooks family and online sleuths believe it highly unlikely that Alonzo wandered out to the relatively shallow creek, tripped and fell only to be left undiscovered for a month. They also believe someone who was at the party knows the truth.

“I just don’t see how they sleep at night,” Felicia Brooks says. “Sooner or later, your conscience is going to get to you.”

The Brooks family says they pushed and pushed law enforcement for answers in the weeks after discovering Alonzo’s body. But even with all their begging, the KBI and FBI had to move on to other cases—Wichita’s BTK killer had recently reemerged—and Alonzo’s suspicious death was ruled a cold case after only one month. “I went up to KBI headquarters in Ottawa and talked with an agent there,” Billy Brooks Jr. says. “He said, ‘We don’t have any more information; the FBI has picked it up,’ and they were basically off the case.”

“If you get assigned a case, my thing is you need to get off your ass, go up there and start questioning people,” Felicia Brooks says. “And for it to be closed within a couple of months—that just doesn’t even make sense.”

After the case was labeled cold, the family remained diligent in trying to apply public and private pressure to the law enforcement agencies. “It was like shouting into a void at times,” Felicia Brooks says. Then, in 2017, everything changed. Angela Ramirez-Cox, who runs the Facebook page “Justice for Alonzo” and coordinates all media interviews for the family, was contacted by someone with the Unsolved Mysteriesproduction team, which was shooting a reboot of the series that ultimately landed on Netflix. The show was years away from hitting airwaves, but producers had slotted the Brooks case for one of the first few episodes. Angela Ramirez-Cox says she was cautious at first.

“I said, ‘If we do this, I don’t want you to get us going and then we don’t hear from you,’” Angela Ramirez-Cox says. “And that’s what happened.”

Then, in April 2019, interviews were scheduled, shoots set up and before they knew it, Alonzo Brooks’ episode was aired.

The case eventually caught the attention of the top federal law enforcement agent in Kansas, U.S. Attorney Stephen McAllister.

“His death certainly was suspicious, and someone, likely multiple people, know(s) what happened that night in April 2004,” McAllister said on June 11. “It is past time for the truth to come out. The code of silence must be broken.”The Netflix episode premiered on July 1 at midnight. The next day, Kansas City magazine gathered with the family in Maria Ramirez’s living room. The family all looked tired and emotionally drained.

“I just started crying,” Maria Ramirez says. The episode has spawned national media coverage and the reopening of Alonzo’s case.

It’s been covered by news organizations from Dateline to CNN, and there are Reddit threads with hundreds of posts theorizing about what happened to Alonzo and calling for justice.

“We just hope this all points us in the direction of who did it—someone who knows someone who did it, someone who knows something,” Felica Brooks says.

But not all that coverage has been productive. Bloggers and true crime geeks all think they know who killed Alonzo and why, prompting them to send death threats to the town and people involved. The FBI, which is actively investigating Alonzo’s death, is offering a one-hundred-thousand-dollar reward to anyone with any information. The FBI exhumed Alonzo’s body in hopes that further study may provide clues. The body was exhumed on July 22; no new information had been disclosed to the family as of press time.

Coverage of Alonzo Brooks’ case isn’t going to end with the Netflix episode. Filmmaker Josh Pratt has been working on a project for about six years and is planning to release an in-depth investigative podcast about what happened.

Pratt, a Kansas native from Paola, remembers Alonzo’s story when it happened in 2004 and felt compelled to look into his story.

“For so many people, especially in Kansas, myself included, going to a barn party or a field party is a rite of passage,” he says. “But no matter what happened, everyone always came home in one piece. Everyone else always came home. Alonzo Brooks did that same thing I grew up doing, but he didn’t make it home.”

Alonzo was just twenty-three when he went missing. His family still has piles of funny stories about him. Sitting in a circle in the living room, Maria Ramirez, Billy Brooks Jr., Felicia and Demetria Brooks, and Angela Ramirez-Cox recount tales of his quirks.

“He was a clean freak,” Felicia Brooks says. “He was very particular.”Alonzo’s older sister talks about how he always had to have everything a certain way, from meticulously making his bed every morning to ironing his money and boxers.

“Wait, wait, wait, wait, tell her about the tattoo,” Angela Ramirez-Cox says. Through fits of laughter, they recount how Alonzo confidently decided to get a tattoo one afternoon in his mother’s house, only to freak out the minute the needle touched his chest.

“Before he got it he was like, ‘I’m a man. I got this! I got this!’” Felicia Brooks says. “So the guy comes over, touches him with the needle and Alonzo jumps up and goes, ‘I’m good.’”

The incident left Alonzo with a singular dot on his chest—which he proudly showed off as his tattoo.

They fondly remember how he loved Budweiser beer, the Chiefs and Newport cigarettes. Story after story, laugh after laugh. But there’s one story they need to know—the truth about what happened in Alonzo’s final hours. “He loved the color red,” Maria Ramirez says. “He had this little red truck, a Hot Wheels one, that he took everywhere when he was younger. I think I lost it in the move from Gardner. I wish I could find it.”