When you think about wine, do you picture Missouri? If not, a new documentary by TasteMAKERS hopes to change your mind.

“I fell in love with Missouri wine early on,” says Cat Neville, the Emmy-winning producer and host of TasteMAKERS who is best-known to KC foodies as the longtime publisher of Feast magazine. “Being so close to wine country is something that I’ve always really loved and seen as an asset.”

The new hour-long documentary, Winemaking in Missouri: A Well-Cultivated History, premiered in Hermann and was screened in St. Louis before its planned national distribution by PBS later this year. Missouri’s often-underrated landscape is the backdrop to the documentary’s exploration of the turbulent history of winemaking.

“The grapes that are native to North America were wild grapes,” Neville says. “When Europeans settled here, they brought their own vines that didn’t do well. Our climate is much less forgiving.”

But climate wasn’t the only problem facing early winemaking settlers. Next up, bugs.

“There’s this bug called the phylloxera,” Neville says. “The native grapes evolved in concert with this grape louse, but the European vines didn’t. When they were infested with this bug, they died. The solution—what created these grapes—was crossing these European grape varietals with the hearty wild grapes.”

These hybrid wines are less recognizable than varieties like chardonnay or pinot noir. The adventure-averse wine drinker risks losing out on delicious Missouri wines like chambourcin, a medium-bodied red, or vignoles, a French-American white grape hybrid that accounts for fifteen percent of all grapes grown in Missouri.

Pre-Prohibition, Stone Hill Winery in the middle-Missouri town of Hermann was the second largest winery in the United States. Prohibition deeply impacted this family-run enterprise for years, as Stone Hill’s current owner, Jon Held, describes in the documentary.

“All the equipment, the casks for aging and storing, were destroyed,” Neville says. “It took until the 1950s for America to reawaken to wine generally. And when prohibition ended, there were no grapes. In Missouri, everything had been ripped out. When you plant a vine, [they] are not mature enough to create grapes for years.”

Despite, or perhaps because of, their fraught history, current Missouri vineyards and wineries are forward-thinking, leaning on the historical importance of grape diversity, sustainability and generational strength.

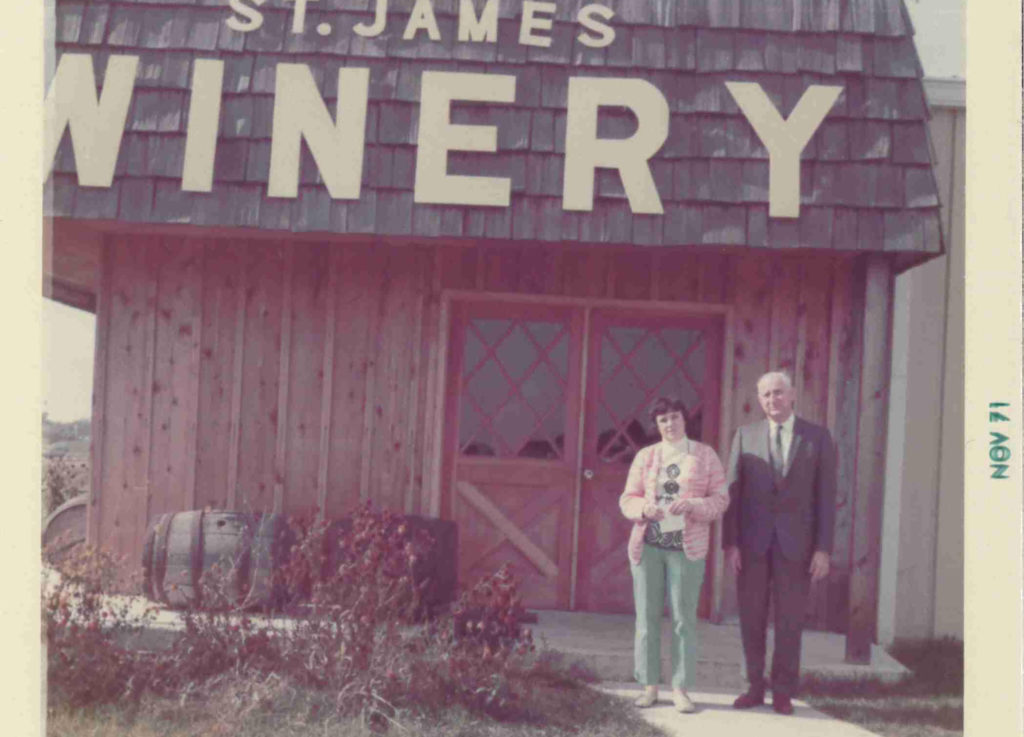

Peter Hofherr of St. James Winery is working to “establish biodynamic farming practices, lessening [their] carbon footprint and reliance on fossil fuels,” Neville says. “Peter [Hoffher] has been clear in saying that where Missouri wine is now is not where it’ll be in a generation. He’s really been out on the forefront of experimenting with new varietals.”

Sustainability isn’t only about predicting climate changes and reducing carbon footprints; these wineries are kept alive by families, passing down their passion for generations.

Winemaking in Missouri is as much a love letter as it is a documentary. Passion for Missouri’s wine and its caretakers is carefully curated by Neville, a longtime advocate for the food- and winemakers of Missouri, who believes “it’s about time Missouri wine got its due.”

Neville describes winemakers as farmers first. “They are starting in the vineyards; they’re babying the vines and deciding when to harvest.

The documentary’s national footprint and PBS distribution could boost the region’s reputation and bring real appreciation back to local makers where Neville believes it belongs.

“I’m completely in love with Missouri wine,” she says. “Where the wineries are located, it’s just gorgeous. It’s a wonderful way to explore the state and to support makers. When you talk about local, this is local.”

WATCH: Winemaking in Missouri: A Well-Cultivated History will premiere on Kansas City PBS on Monday, November 28 at 7 pm. It will air multiple times in December.