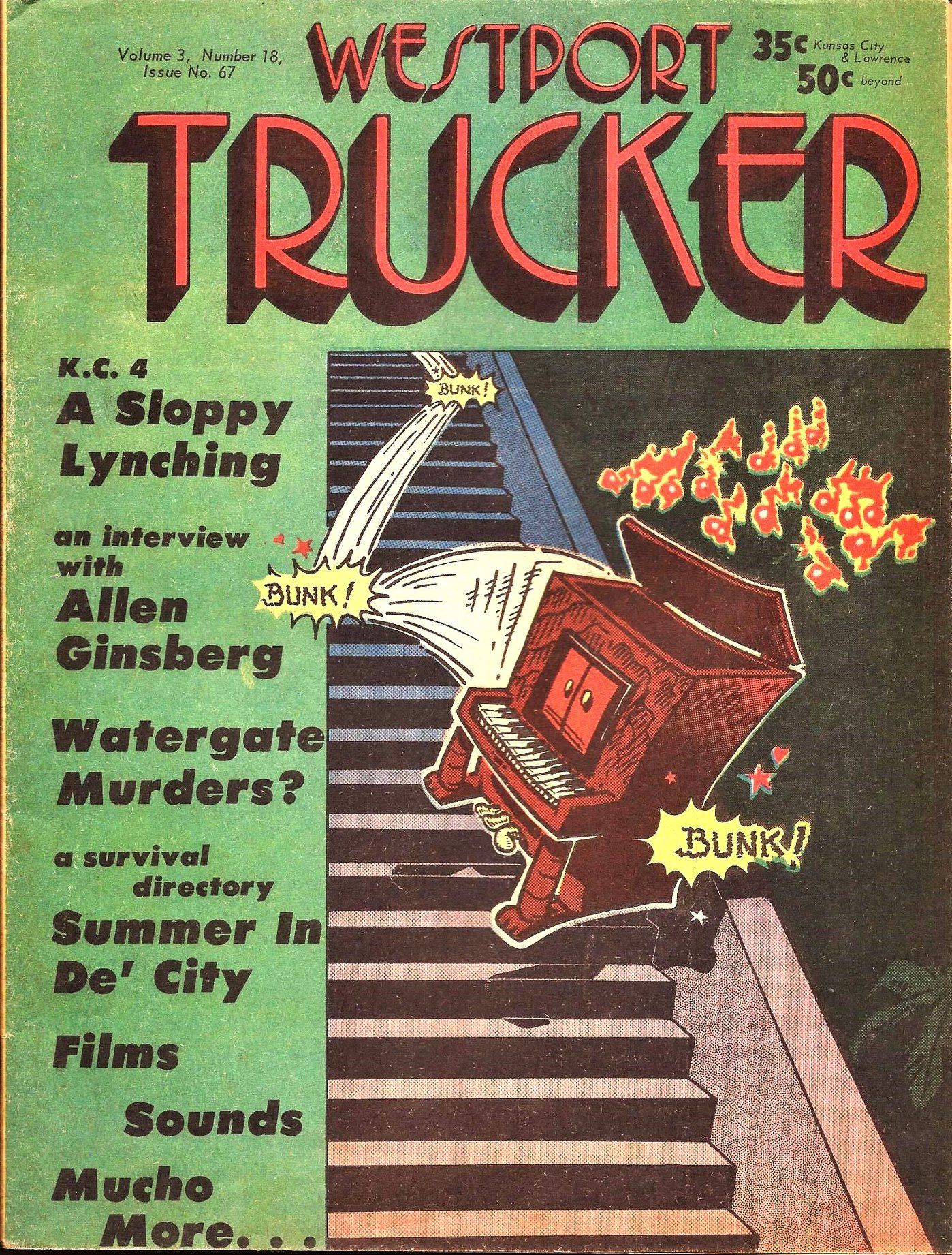

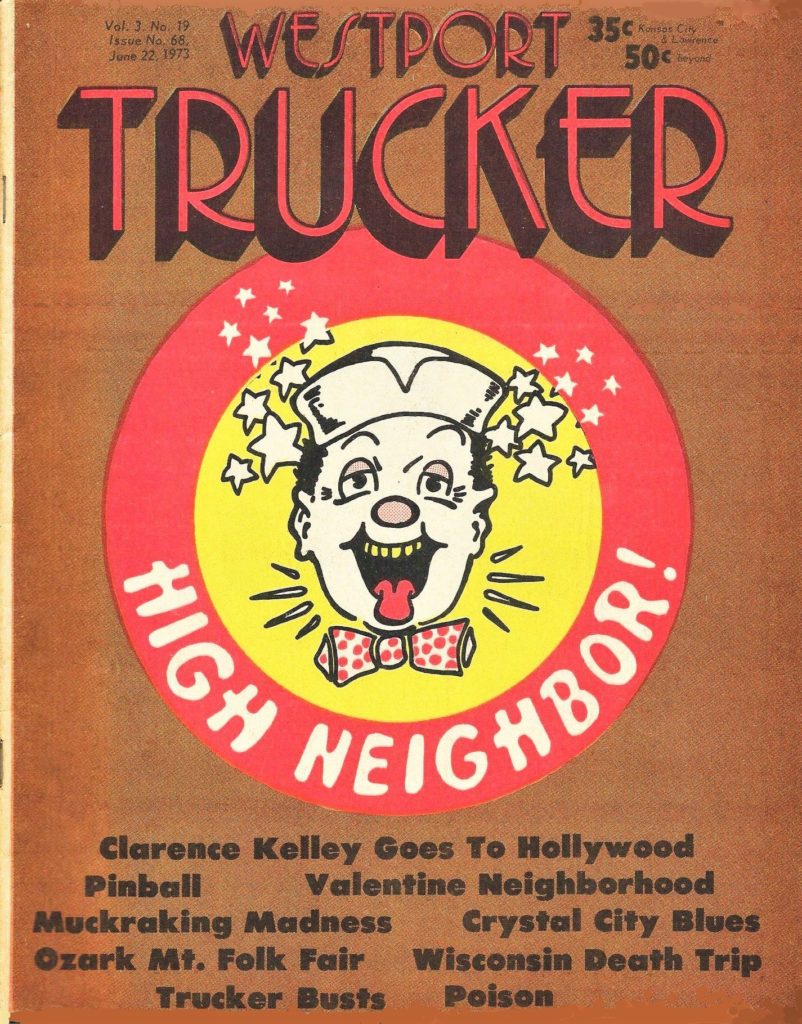

In the Depths of LaBudde Special Collections at UMKC’s Miller Nichols Library sits a growing stack of the Westport Trucker, their covers scattered in neon colors and psychedelic designs, printed on crinkled paper that is now yellowing.

That stack will grow just a little taller if Chuck Haddix can help it. Haddix’s title at the library is Curator of Marr Sound Archives in Special Collections, but he’s better known around town as Kansas City’s premier cultural historian, the host of a well-loved radio show and the author of a biography about Charlie Parker. Haddix’s latest project at the library is an attempt to assemble the only complete collection of Kansas City’s earliest and most notorious under-ground newspaper, the Westport Trucker. The Trucker, which was published between 1968 and 1974, influenced an entire generation—including Haddix himself.

“The Trucker is very important to me—it’s the stuff that shaped my life and career and sparked my interest in writing,” says Haddix, who grew up north of the river but bought the newspaper at a shop called Tiny Tim’s Magic Circus in Westport. “In those days, there was no internet. You had these underground radio stations, but this is what brought the community together. This is where you found out who was playing Volker Park that week.”

If you know what Volker Park is, you can thank the Trucker—the publication is responsible for popularizing the colloquial name for Theis Memorial Mall in front of the Nelson-Atkins Museum.

About a year ago, Haddix started working with the man behind the paper, Dennis Giangreco, on the collection. Giangreco, who publishes under the name D.M. Giangreco, is also something of an institution—he moved from KC to NYC and founded a little magazine called High Times before becoming an eminent military historian and author.

Dennis Giangreco’s career started in the summer of 1966 when he hopped on a Grayhound to San Francisco at fourteen. The teen spent the following summer out there, working odd jobs for Family Dog Productions, parent company of the Avalon Ballroom, and heading post-show cleanup for the Rolling Stones’ infamous Altamont show.

Giangreco left school after his junior year at Center High School to commit his time to booking acts, renting out music halls around Kansas City and negotiating with the city to hold weekly Sunday concerts in city parks starting in 1969. The first rock concert at Volker Park just the year before featured an act called the Amelia Earhart Memorial Flying Band—whose lead vocalist, Sylvester James, later became the city’s mayor.

In 1969, Giangreco worked as a top-selling street vendor at the Kansas City Screw, an underground newspaper that printed ten issues before a merger with what Giangreco calls “a somewhat more doctrinaire publication out of Lawrence,” Reconstruction. The resulting paper was Vortex. Most of the Kansas City staff bailed, and Giangreco spent time in San Francisco and Denver before returning to KC, rounding up most of the original staff and changing the name of the publication to Westport Trucker.

“The big catch phrase at the time was, ‘Keep on truckin’,’” he says. “It was built off of [cartoonist] Robert Crumb’s whimsical idea of: Movement! Action!”

The successful Trucker, which Giangreco says printed ninety issues from the tail end of 1968 through the spring of 1974, operated out of a few different spaces in Westport surrounding areas over the years. The paper was sold at local head shops and by street vendors.

“After about a year, we never had an edition that sold less than four thousand copies,” he says. “After the third year, we never had an edition that sold less than seven thousand copies.”

Alternative content and inconspicuous headlines like “Did Waterbuggers Assassinate JFK?”, “Tums Spelled Backward Is Smut” and “Zippies Indicted For Miami Firebomb” attracted an audience that ranged from hippies to the Mission Hills set, according to Giangreco.

The paper’s street vendors were routinely arrested or detained when selling the paper on the Country Club Plaza, with detainees being charged for “interrupting pedestrian traffic” and being taken to a precinct on 63rd Street in Brookside to be locked up for a few hours.

“When that would happen,” Giangreco says, “the first person you call is not the attorney. The first person you call is the office or Tiny Tim’s Magic Circus, which was our distribution point on Broadway. And they would round up more vendors.”

The police eventually let up on the Trucker team, Giangreco says. “One judge said: ‘I don’t want to see you continuing to bring this stuff to us. I just don’t want to see it. It’s wasting everybody’s time.’ After that, we were pretty much left alone.”

Former Trucker National Affairs Editor John LaRoe says his pay included a third-floor attic apartment at the newspaper’s office, on Harrison Street at the time, and he’d often host contributors passing through town. (The Trucker also had staff out of New York City, where Giangreco moved in 1974 to start High Times).

“I think one of the things that is remarkable about the Trucker is that it really was about West-port,” LaRoe says. “Then, it was probably even more of a dynamic neighborhood. And there were actually a lot of older people, people that are my age now, reading it. I think at one point even my mother helped distribute the Trucker.”

Haddix’s efforts to collect every edition of the Trucker—“Before your grandkids throw them in the trash…” is the campaign’s tagline—is spreading rapidly over Facebook. Meagan Glass, also a longtime Trucker admirer and once patron of Volker Park and Cowtown Ballroom concerts, has spent the last year hyping up the UMKC Trucker collection by posting in community Facebook groups and branding herself as Giangreco’s “office manager.”

Glass is taking this role seriously for now, but her husband is hoping she’ll cut back soon. She and Giangreco say that Tommy Greene, former Trucker bee and Kansas City rock history aficionado, is supposed to eventually get on Facebook and take over the outreach.

“Greene has been promising for almost a year to start handling the page but, as I’ve said before, I suspect that it will be later rather than sooner,” Glass says. “My poor, neglected Bill says, ‘It can’t come soon enough for me!’”

But, as it goes with so many of these lax hippie chain-of-command operations, Glass is taking the wheel until further notice.