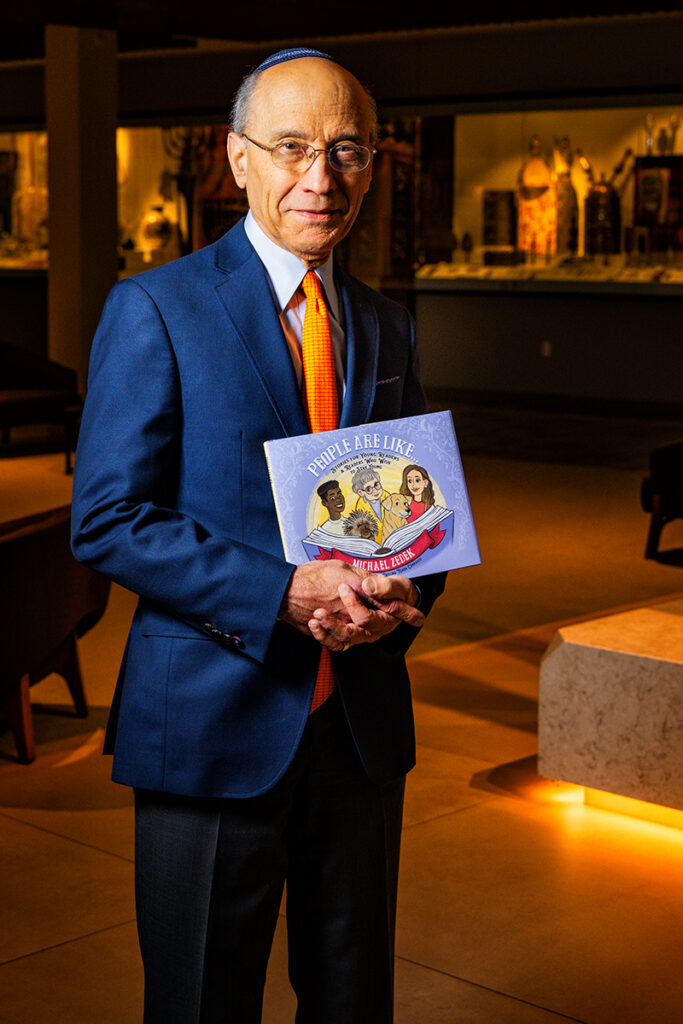

Jewish culture is built on books—writing them, reading them and talking to others about them. No one exemplifies the Jewish love of learning more than Michael Zedek. He’s the Rabbi Emeritus of both Congregation B’nai Jehudah in Overland Park and Emanuel Congregation in Chicago and is currently the Rabbi-in-Residence at St. Paul’s School of Theology in Leawood. Zedek has written a pair of books; his latest is a tome for children, People Are Like …: Stories for Young Readers and Readers Who Wish to Stay Young.

We meet to talk about the book in his airy Leawood home. The winter afternoon is crisp and bright. Sun pours through tall windows into a living room filled with plants and white furniture. Big rugs cover glossy hardwood floors, and a small collection of ancient Levantine artifacts adorns a set of built-in shelves along a far wall.

We sit with tea. Zedek, trim, bald, in a gray quarter-zip, is gregarious and loquacious. He is a charismatic presence with a deep need to share, connect, think and laugh. Before discussing the book, we kibbitz for a while. We talk, for instance, about his very popular class at St, Paul’s, Genesis as a Rabbi Sees It, which he describes as “an introduction to the 3,000-year encounter that Judaism has with these sacred texts” and “how they impact who and what we are.”

We talk about the Sabbath, and he mentions Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel’s notion that the weekly day of rest can be “a cathedral in time.” The Sabbath, Zedek says, is meant to be a sacred experience in time, the way that churches, mosques and synagogues create a sacred experience in space.

We talk about Kansas City, where Zedek has lived on and off for the better part of 50 years.

“Having grown up in New York,” Zedek says, “one gets used to the notion that there are certain things we just can’t fix, no matter what. We’re just going to have to learn to live with them. One of the great qualities of the Jewish community here and the larger community of Kansas City is that there’s no problem that we don’t think we can fix, even if we’re wrong. Which I think is a wonderful way to be wrong!”

Finally, likely to the rabbi’s great relief, we talk about his book, People Are Like …

He starts by pointedly noting that the book’s proceeds will go toward scholarships for needy kids. Then, hilariously and with purpose, he lists all the local, brick-and-mortar shops where the book is available (including Rainy Day Books, The Learning Tree, Turn the Page, Revocup Coffee Shop, Made in Kansas City and the B’nai Jehudah gift shop) before finally, almost reluctantly conceding that his book can also be found on Amazon.

The genesis of the People Are Like … is murky, even to Zedek himself. “No one knows all the reasons we do anything,” he laughs. “But I’ve been encouraged by so many of my students to put the stories that I use to convey values into a written form.”

To illustrate those values, he tells a tale that’s not in the book—a story of Rabbi Nathan, who lived around the second or third century.

“A group of rabbis were debating whether it’s permissible to attend the gladiatorial combats of Rome,” he starts. Most of them thought people should avoid such ferocity because “it brutalizes all, including the spectator.”

But one, Rabbi Nathan, said that we have to attend—because, quite simply, someone has to stand up for kindness. “When the crowd shouts for the blood of the defeated gladiator and goes thumbs down,” Zedek says, “our job is to shout thumbs up.”

All the book’s stories have that idea as a common thread. Whether they are about porcupines looking for warmth, a hippo teased for his size or a grove of Redwoods with interwoven roots, the overarching theme of the book is finding ways to connect, care and lift each other up.

Namely, the stories convey concern about empathy and compassion.

That need for kindness is not just the main theme of People are Like … either. It’s the essence of Zedek’s life’s work. Our job as human beings, he believes, is to find the divine in ourselves and others by leading more empathetic and compassionate lives. He illustrates, of course, by telling another story.

Back when he was still at the seminary, one of his fellow students asked a teacher how they could possibly come up with a topic for a sermon every single week. The teacher said that’s not the problem. You really have maybe one or two sermons—one or two themes that really matter to you. The critical thing is to find out what they are.

“After 51 years of at least one sermon a week, he was right,” Zedek says. “My sermon is that there’s holiness all around us. There’s a sacred dimension in us. Now get to work.”