When hospitals sent volunteers home in March 2020, nobody knew if (or how) they’d return. Now, more than five years later, the answer is clear: Hospital volunteers are back, even if the day-to-day doesn’t look the same.

“We didn’t have volunteers for almost nine months,” says Nicki Johnson, director of philanthropic volunteer services and in-kind giving at Children’s Mercy. When programming resumed, the hospital took what she calls a “slow, steady course,” bringing back familiar faces first. Some never returned, though; immunization requirements deterred some, and for others, nine months of isolation had taken too much of a toll in their rhythms. Many retirees, which make up a large chunk of hospital volunteers, left Kansas City or became snowbirds.

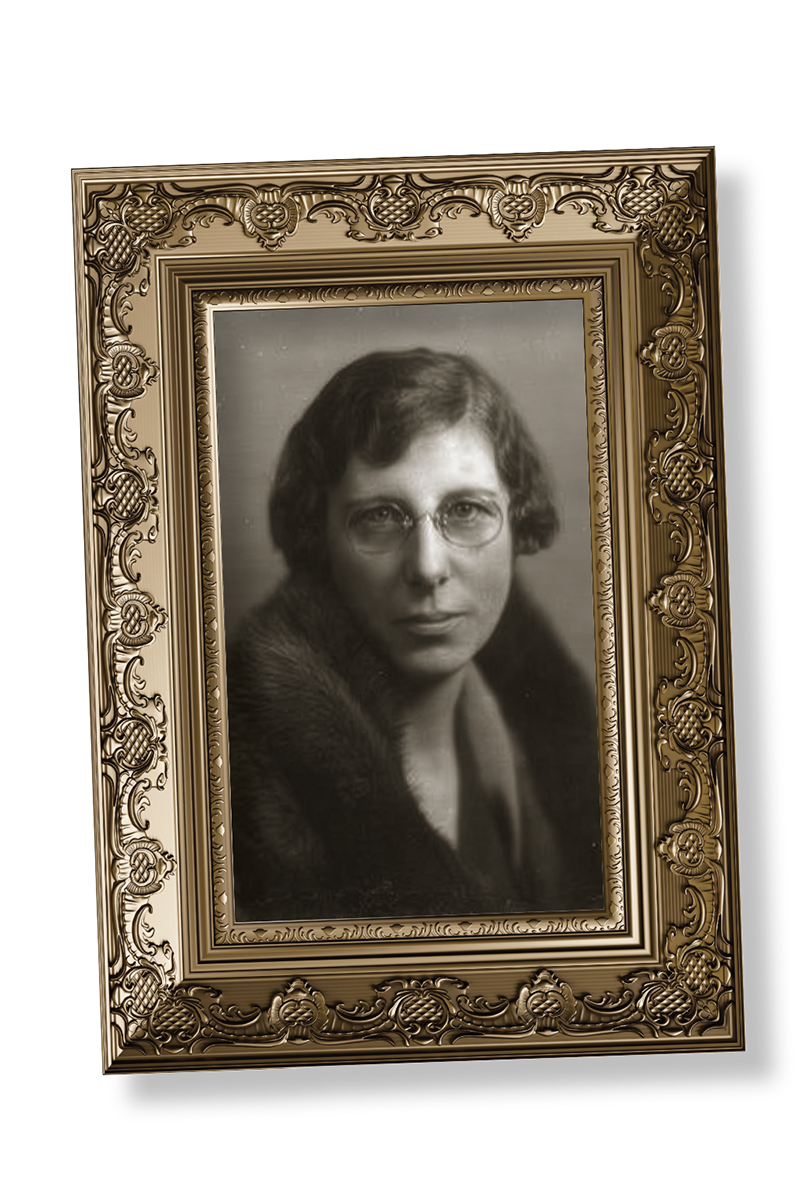

At University Health, the story remains the same but with its own variations. Valinda Fisher-Hobson, senior director of community management, recalls volunteers calling in during the shutdown asking when it was time to come back.

“Some of them were a little reluctant because we still had to wear masks,” Fisher-Hobson says. “And the isolation really hurt a lot of people.” UH had to rebuild from zero, reaching out to each veteran volunteer by email and phone. Some older volunteers couldn’t drive to the hospital anymore. Others simply couldn’t function in the new reality of health care.

What emerged from the rebuilding of volunteer services wasn’t just a return to normal but a reimagining of what volunteer services could look like.

At Children’s Mercy, Johnson and her team began to use technology even more, and the practices stuck. They’ve found creative ways to use CCTV to do virtual activities like bingo and storytimes. Volunteer-led playroom gatherings have evolved into volunteer-made craft kits delivered bedside. Potential germ vectors, like shared Uno decks and costume crowns, have disappeared entirely and are replaced by “happy kits” assembled by volunteers.

Along with a shift in everyday volunteer opportunities, hospitals are finding that the kids who lived through Covid are showing a keen interest in health care as a career. “Kids were introduced to it just by the state of the world at that time, and they are really interested,” Fisher-Hobson says.

Such is evident by UH’s summer health-care camp. “We target high school students, and we have a Health Sciences District Academy offered at our Hospital Hill location,” says Cathrine Harland, corporate manager of volunteer and retail operations. “And then we offer our Blue Spring School District health-care camp at Lakewood. About 45 students come through total, and we give them the experience and exposure of a career health-care pathway.”

Hospitals around the city are working to explore more community engagement opportunities and expand programming in ways that feel both innovative and necessary. University Health plans to welcome two miniature horses to their pet therapy program, a creative expansion that Fisher-Hobson says might not have existed without Covid forcing hospitals to rethink everything.

Children’s Mercy’s Johnson says that the hospital is also pragmatic about the future. “Our goal is really focused on our commitment to engaging our community in learning about Children’s Mercy,” she says. Her goal: Get volunteers in the door once, let them “experience Children’s Mercy, to feel it, to know it,” and hope they stay.