Missouri and Kansas are dotted with famous and not-so-famous spots of historical significance to America’s great westward expansion. Kansas City and its environs were a strategic starting point for many seeking opportunity and heading west to manifest their own destinies

Nicodemus, Kansas

Following the U.S. Civil War, the recently opened western country provided a sense of opportunity and hope for many newly freed slaves. While many freedmen fled to the rapidly growing cities of the northeast, some smaller groups, like the Exodusters, opted for life on the Kansas prairie instead.

At this time, Kansas had earned an association with the earlier abolitionist movement and free-state heroes like John Brown. And for some groups like the Exodusters, Kansas was seen as their promised land.

In 1877, a group consisting mostly of former slaves from Kentucky established a small western-Kansas town on the northern bank of the Solomon River and named it Nicodemus. While the settlers of this town were not by definition Exodusters, they did share the same hopes and dreams of opportunity on the Kansas prairie, and they also faced many of the same challenges.

Although Nicodemus did experience a brief period of growth, small-scale farming in the semi-arid Kansas uplands proved too difficult for many of these pioneers who often came without the resources to operate farms long-term. This, coupled with the failure to attract a major railroad line to the town, led to Nicodemus’s steady decline by the end of the nineteenth century.

Today, Nicodemus is a designated National Historic Site. It has a bookstore and museum and is home to a population of about fourteen.

Hell on the Plains

There is perhaps no town in Kansas that better exemplifies the state’s Wild West roots than Dodge City, once dubbed “Hell on the Plains.”

An important stop for pioneers on their journey west, the town was a hub for buffalo hunters, cowboys and gunslingers and all the depravity and lawlessness that came with them. The streets, often lined with buffalo hide ready for market, were a frequent spot for gun fights. Saloons and brothels were staples of the local economy, offering a steady source of entertainment for the raucous cattle drivers that came into town.

The lawlessness became so bad that legendary lawman Wyatt Earp was brought in to restore order. Lawlessness slowly faded from the town, along with its primary economic mainstay: cattle.

In an effort to control the infectious diseases that often accompanied cattle coming up from Texas, the Kansas State legislature all but banned the cattle drives throughout the state, so the cowboys set their sights further west. They took their cows, guns and vices and got the “hell out of Dodge.” Over the next one hundred and fifty years, Dodge City grew into the typical western Kansas town as we know it today.

Jail Bird

From 1859 to 1933, Independence had the honor of playing host to Jackson County’s population of incarcerated scoundrels and ne’er-do-wells.

Now a tourist attraction, the 1859 Jail Museum once housed countless local and Civil War military criminals within its thick limestone walls. Perhaps the most prominent prisoner was Frank James, the brother of the metro’s most infamous Wild West outlaw, Jesse James.

Frank called the jail home for six months in 1882, during which time he enjoyed such fineries as carpets, furnishings and artwork and enjoyed privileges like freely roaming the jail and hosting card games in his cell after dark.

A long way from its time as a jail, today the building houses a history museum open for tours where visitors can visit Frank James’s decked-out cell.

National Pony Express Museum

The rapid westward expansion of the United States brought with it a number of logistical challenges during a time of still-early industrialization. Where the treacherous Rocky Mountains and defensive Native Americans posed perilous obstacles for transportation of goods and people, the complete absence of settlement and infrastructure made communication nearly impossible.

Three prominent Missouri businessmen already involved in the western shipping and freight industry created the now-famous Pony Express to help move mail across the new territory.

A team of eighty riders carried mail between one hundred and ninety stations spaced out about ten miles apart between St. Joseph, Missouri, and Sacramento, California. At each station, a rider would switch to a fresh horse and continue on his journey across the untamed expanse of the Wild West. This system allowed mail to travel between Missouri and California in a record-breaking ten day period. The horses, while not exactly ponies, were small and zippy, as were their riders, young boys who could not exceed one hundred and twenty-five pounds. One of these little cowboys went on to become legendary Wild West showman William “Buffalo Bill’’ Cody.

While the company’s brief eighteen months of operations ceased with the advent of the first transcontinental telegraph system in 1861, the mythos of the Pony Express had already been interwoven into the fabric of Western legend and lore.

Today, the Pony Express National Museum is housed in the old Pony Express Stables in St. Joseph, where the first rider set out in 1860.

Buffalo Soldiers

First established as regiments for Black cavalry soldiers following the Civil War, the Buffalo Soldiers not only served in several U.S. conflicts but also played an integral role in the protection of westward travelers and pioneers on the great frontier.

The Buffalo Soldiers built and assisted in the development of various kinds of infrastructure including roads, forts, telegraph lines, railroads and wagon trains.

The Wild West was a hostile country, and United States authorities could not have ensured security for those pioneers had it not been for the contributions of the Buffalo Soldiers. Today, a monument to the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments of the U.S. Army can be visited in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, the home of the Buffalo Soldiers.

Kansas City’s Red Light District

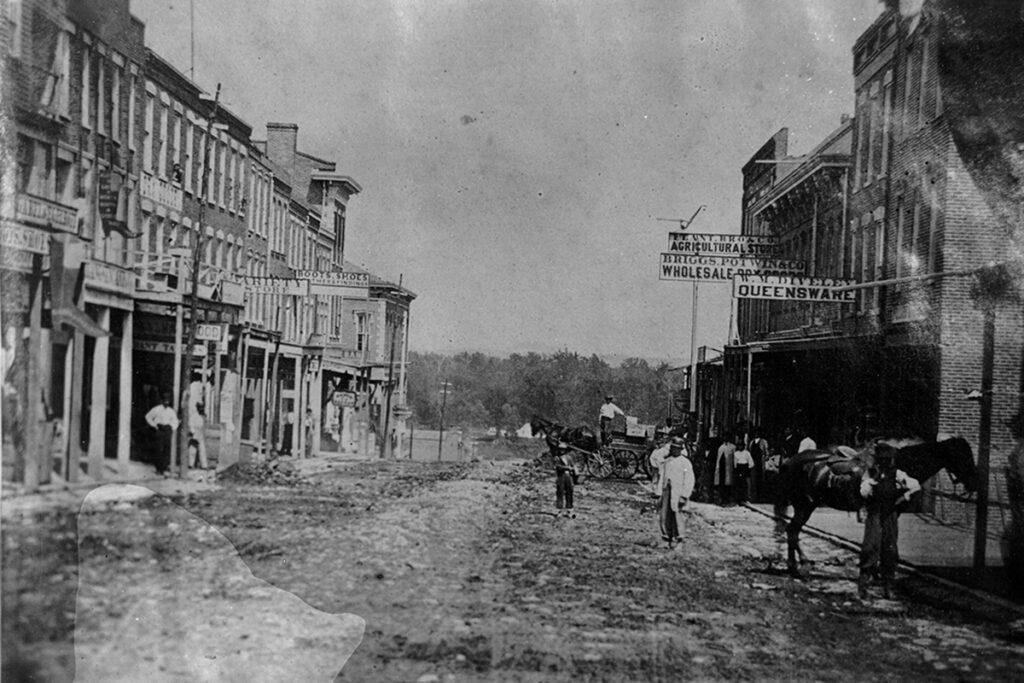

The city was often the last stop before venturing into the great unsettled expanse of the prairies—a place where men could rest, wet their whistles, win (or lose) some money gambling, gather supplies and enjoy a hearty meal and perhaps the company of a young lady.

The neighborhood now known as the River Market and home to many young professionals was once this city’s very own red light district. In the late nineteenth century, a walk down Third Street would have offered a glance of women standing on wooden-planked sidewalks donning colorful dresses in front of a promenade of bustling bordellos.

The most infamous of these establishments was that of one Miss Annie Chambers, Kansas City’s most prominent madame. Miss Chambers operated a twenty-five-room luxury “resort” at Third and Wyandotte from the 1870s until the 1910s, when the city began its widespread moral clean-up effort, and establishments like that of Miss Chambers faded into the dark recesses of KC’s past.