Oouumphhh.

There’s a grunt from the front of the jon boat as Jim Hoke’s treble hook finds the meaty flesh of a spoonbill swimming in the muddy depths of the Lake of the Ozarks. As his 150-pound braided fishing line zings down into the green water, Hoke suspects he’s successfully snagged one of the monstrous prehistoric fish that brought him out here. The spoonbill grows an average of 5 feet long and has a trophy-ready sworded snout that brings anglers from across the country to Warsaw, Missouri.

A moment after his hook snags, Hoke feels the telltale jolt of animalistic struggle — the flounce, he calls it — as the ancient beast tries to peel away from the barb lodged in its back. Hoke starts reeling, intently focused on the fight to get this massive fish close enough to the boat for his buddy Gayle Wells to impale it with a gaffing hook.

Hoke, 62, is a retired maintenance man from West Plains, Missouri, just north of the Arkansas border. Every spring for the last quarter-century, he’s taken three weeks off work to come here and camp in an RV so he can trawl the waters below the Truman Dam.

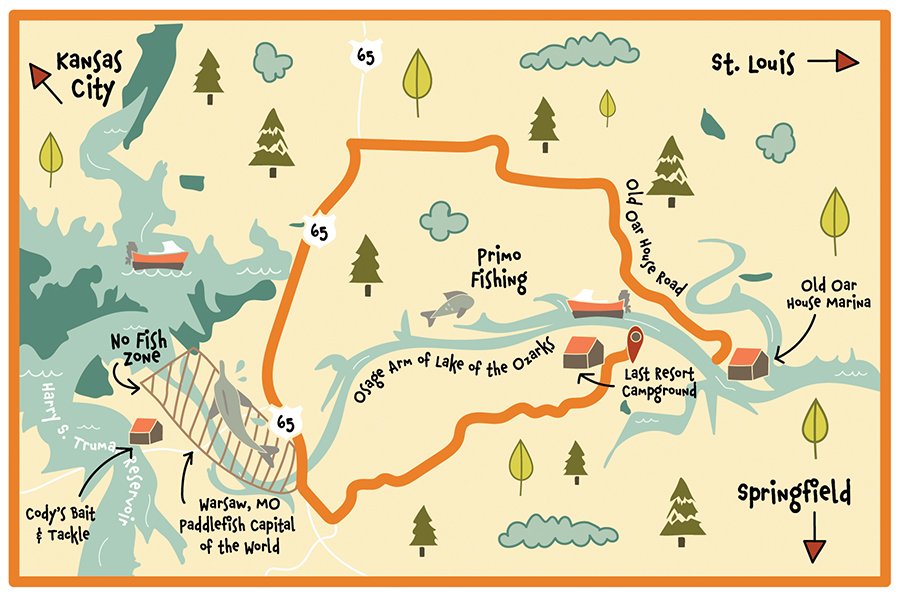

Hoke mostly fishes with Wells. Their home base is Last Resort, a campground with a private dock on a shallow spot on the northern edge of this serpentine 93-mile lake. They fish up and down a stretch called the Osage arm — Wells at the wheel, Hoke standing up front — lifting and lowering their poles in the same rhythm, aiming to catch one of their hooks on the filter-feeding fish growing fat off the plankton in this man-made lake.

Under Missouri law, the men can catch two mature spoonbill every day between March 15 and April 30. They aim to snag their daily limit early and then cast for crappie or catfish. It’s a way of life for the men — and the bulk of their protein for the year. After six weeks of reeling in 120 pounds of fish per day, their deep freezes are stuffed with spoonbill filets. Both men eat the white, flakey flesh year-round.

“You can grill them, you can fry them, you can pressure cook them,” Wells says. “Some people say you can bake them. My mom tried to bake them once. She said, ‘That’s a good way to ruin a good fish.’”

When it comes to the spoonbill’s eggs, the biological imperative that drove these fish upstream to spawn, the men have no interest. Any time they catch a female, they immediately scoop the little black pearls back into the water on the side of the dock.

Add a pinch of salt, and those eggs become precious black caviar. One large female fish on the Lake of the Ozarks can have $4,000 worth of caviar in her belly.

“We’ve thrown away millions of dollars of the stuff,” Hoke says. “Millions.”

Not everyone does likewise.

The chance to nab such a big, valuable fish is drawing a new breed of angler to this corner of the Ozarks.

The good ol’ boys worry that their little oasis will be overrun by caviar-mad Eastern Europeans who don’t value the fish the same way they do. Some of the Russians were sent here by the mafia to poach fish eggs and smuggle them overseas, they say. Those rumors were strengthened by a major bust of poachers, which sent a big ripple across these waters. The culture clash has boiled over from time to time, such as when the clerk at a bait shop pulled a .40 caliber pistol on two Russian shoppers who wouldn’t follow his commands.

The spoonbill, also known as the American paddlefish, appears in the fossil record 75 million years ago, when velociraptors prowled the earth. They’ve changed little since. These oddball creatures look like swordfish with their snouts pounded flat. Spoonbills have tiny eyes and use sensors in their snout to navigate as they hoover up plankton on the bottom of rivers.

Although the spoonbill once ranged up to New York and a few can still be found in Montana, today they’re concentrated in the lower sections of the Mississippi and Missouri river systems. The spoonbill is the second largest freshwater fish on the continent. Its cousin, the white sturgeon of the West Coast, is the largest. Good luck catching one of those — the threatened species is tightly protected.

Another cousin, the beluga sturgeon of the Caspian Sea, is the world’s largest freshwater fish. The beluga is also the source of the most prized caviar on earth. Overfishing has driven beluga to the brink of extinction. In 2005, the United States banned the importation of its caviar. Aficionados and crooks both started scrambling to find substitutes.

They ended up in the Ozarks. Whether it’s the strong economy, changing tastes or immigration, Americans are eating more caviar than ever before. The U.S. imported $17.8 million worth of caviar in 2018, which is more than double the $7.6 million imported in 2014, reports the Wall Street Journal. Most commercial caviar is now farmed, and much of it now comes from China.

The spoonbill, as it happens, has roe fairly similar to beluga. The spoonbill’s roe are also small, firm and on the color spectrum between grey and black. Although they’re a bit earthier and less buttery than the Russian original, they’re a fine substitute given the situation.

Other states in the region have spoonbill, but Missouri has both the most liberal laws for snagging and a uniquely effective fishery. Gluttony and sloth have made Warsaw, Missouri, the spoonbill capital of the world.

In 1931, the opening of the Bagnell Dam on the Osage River created the Lake of the Ozarks. That disrupted the natural upstream migration of the spoonbill, trapping the fish in a reservoir. In 1979, the Truman Dam opened, creating a second reservoir and severing the spoonbill’s migration route to the spawning grounds of the rock beds and shallow coves of the upper river. Without intervention, the spoonbill would have died off in the area. Instead, forward-thinking state officials developed the first breeding and stocking program for American paddlefish.

Presently, 38,000 juveniles are stocked in the state annually at a cost of $100,000 — about $2.50 per fish. It typically takes about seven years for a fish to grow to keeper size in the northern Ozarks. The species can live to be up to 50 years old.

Spoonbills are stout migratory fish that can travel 2,000 miles through a river system. But they’re also very content to be couch potatoes, says Trish Yasger, fisheries management biologist for the Missouri Department of Conservation, who writes the state’s spoonbill fishing forecast by tracking water temperature and speed to cue anglers in on where to drop their hooks. These fish love the calm, shallow waters between the two dams.

“They’re not having to fight the flow in the open river, and there’s more food,” she says. “They just get big and fat in those reservoirs.”

Spoonbill can be found in Mississippi, Missouri and Ohio, but snagging them is tougher in bigger water. You’re just as likely to snag an old tire.

In the Lake of the Ozarks, spring flows from the dam trigger the spoonbill’s natural spawning instincts, and they swim up toward the dam, gathering in shallow water and sufficient numbers to make snagging a viable sport. For the six-week season, it becomes an obsession for some.

Gayle Wells, 67, is from Belgrade, a tiny Missouri town of 200 people that’s 85 miles southwest of St. Louis.

Wells, who sometimes labels himself a hillbilly, grew up fishing. His family all fished, too. But it wasn’t until about 30 years ago that any of them sought out spoonbill.

“Nobody liked spoonbill,” Wells says. “The first ones they got, they had no idea about them. So they skinned them like a catfish and nobody liked them. They said ‘Oh my God, we don’t want no more of that.’ Then they learned to get that red meat off them.”

Spoonbills have sections of flakey white flesh and dark reddish-brown flesh. The red meat on the spoonbill is, by all accounts, foul. “Like motor oil,” Hoke describes it.

Some tell stories, possibly apocryphal, about the scrappiest of mountain folk finding a way to wash it enough to eat the red. But most local fishermen take great pains to carefully trim every tiny speck off and toss it back into the river. Once folks figured out the white meat was good eating, Wells says, they started snagging. And they only stop when the clock strikes midnight at the end of the season.

Because they’re filter feeders, spoonbill have no interest in anything on the end of a hook. So the preferred method of “spoonbillin’” is trawling up the river, guided by a fishfinder, dragging a heavy weight and several hooks. The old timers put a ball on the butt of the rod and lift the pole up and down in the hopes of snagging prehistoric prey. Guides and newbies, by contrast, tend to use plastic “dipsy divers” that eliminate the need to repeatedly pull the pole.

There’s a slot-machine appeal to the act: The spoonbills are laying down there, and you just have to pass over them and yank up at the right time to catch the biggest fish of your life.

Matt Gardner has quickly found himself hooked on the sport.

Gardner, 44, is a retired Kansas City, Missouri, police sergeant. In 2015, he moved his family from Liberty, Missouri, to the Lake of the Ozarks, where they’d previously vacationed. He bought Last Resort outside Warsaw as a place to live and work as a middle-aged retiree.

When he bought the campground, Gardner had no idea what a spoonbill was. He took over the property in June, after the season was over. About six months later, he started getting calls from people who wanted to camp and fish during the chilly early spring.

“This is its own camping culture — its own deal,” he says. “These guys, they come down, they set up their own fish-cleaning stations at their campers. It doesn’t seem to really matter what the weather is — cold, rainy. As long as there’s not thunder and lightning, they’re out there.”

The appeal of the sport was not immediately obvious to Gardner.

“I saw them and I thought, ‘That don’t look fun to me. That looks like solid work,’” he says. “Last year, I went out with Gayle and Jim, and I caught my first fish. I said, ‘Boys, we’ve got a problem.’ They said ‘What do you mean?’ and I said, ‘That was fun.’ This is addictive.”

This year, Gardner caught a 78-pounder with “three or four Walmart sacks worth of eggs” in it. On the retail market, those eggs would be worth thousands. He threw them out.

“I don’t eat that stuff,” he says. To deter poachers, Missouri law stipulates that the eggs of the spoonbill cannot be unattached from the fish until it’s at a private residence and that the processed caviar can’t leave that premise thereafter. Because Gardner owns property on the lake, he’s uniquely positioned to bust out the mother of pearl spoons and gorge himself on tens of thousands of dollars worth of shiny black roe — or to throw parties for others who indulge.

The retired cop has no interest.

“I don’t want those kind of folks here,” he says, suddenly transforming back into the cop about to write you a speeding ticket. “I don’t want anybody here that’s going to be doing that kind of stuff illegally, that’s for sure. I had Russians down here using my boat ramp the other day, but I think they were legitimate spoonbillers… I would hope nobody’s doing anything illegal on my boat dock, because I will confront them.”

There have been a few confrontations between Russian caviar-seekers and good ol’ boys in recent years. In February, the journalism site Longreads.com published an investigative piece on spoonbill snagging that begins with an anecdote in which the clerk at a Warsaw bait shop draws a firearm on two Russian “poachers” with an “entitled attitude” because they were shopping for poles before he could put price tags on them.

Cody Vannattan, who owns the shop, isn’t sure whether his clerk actually pulled a gun or not — folks around Warsaw are known for telling fish stories — but his shop has had only a few Russian customers this year.

“We hadn’t seen any all season until yesterday,” he said in early April. “That might have had something to do with that magazine article. If that got back to them, they might have stopped doing business with me.”

That is not a welcome development. “The Russians” as they’re called in Warsaw (although they’re sometimes Ukranian, Georgian or Azerbaijani) tend to show up in these hills without rods or tackle.

“They spend a lot of money,” Vannattan says. “A lot of money.”

Vannattan is unique among locals in that he doesn’t believe there was much of a story to the Russian poachers. He blames the media for “blowing it up a lot bigger than it was.”

“They had one bust last year,” he says. “Everybody was trying to say it was Russians. There was 17 fish. Well, it was eight guys; they were one fish over their limit. You can’t believe half the s— you read. Straight up.”

There’s been a lot of sensationalist and irresponsible reporting on spoonbill poaching, to be sure. But area law enforcement has also chummed the water, starting with a 2013 press release in which the state of Missouri said it busted a “major paddlefish poaching operation” which involved “more than 100 suspects from Missouri and eight other states.” The press release suggested —but did not openly state — that the busts were tied to a mafia trafficking operation.

Operation Roadhouse involved setting up a fake bait shop with its own pier that was outfitted with hidden cameras to capture poachers bragging about their conquests. To make the arrests, 125 armed state and federal agents were dispatched across several states.

The spoonbill story proved to be a shimmer shad to national journalists, who can’t resist a good mafia story or a good Ozarks story — let alone both at once. “How the Russian Mob is Linked to Illegal Fish Eggs from Missouri,” blared Field & Stream. The headlines only got clickier from there.

Locals have embellished things, too, twisting details as the song of the spoonbill grew to become folklore fit for the Ozarks. Around Warsaw, you hear stories about a man being busted at the airport with a suitcase full of caviar bound for Kiev. They say the investigation had to be halted because it just kept climbing higher into the world of Russian organized crime and there was “no end in sight.”

The actual situation is more nuanced. The final tallies were 256 citations issued to 112 people in 19 states. The government collected $83,700 in fines and suspended fishing privileges for 35 people, including one man who lost his fishing license for life. Two people were put on house arrest for three months each.

Operation Roadhouse cost millions — all to protect a fish that costs $100,000 a year to stock and which would otherwise have disappeared from the area because dams destroyed their natural spawning grounds. As the author of the Longreads.com piece concluded after parsing 625 pages of court documents, there was no evidence of international criminal conspiracy. Rather, the guys who were snagged seem to have been breaking the law to have lavish parties for family and guests.

Several out-of-state men plead guilty to violating the Lacey Act, a federal law which prohibits transport or sale of illegally obtained wildlife. But none of the guilty pleas required them to testify against anyone up the chain of command in the Russian mafia — probably because they appeared to be rogue actors hoarding eggs for their own use.

“Why would I want to sell it?” one of the Russians asked incredulously during his interrogation. The only evidence of possible international trafficking to thus emerge is the presence of empty tins of exorbitantly priced imported caviar at campsites in the Ozarks. Missouri officials take this to mean that American paddlefish caviar is being processed and tinned for export on the black market. “It’s not hard to put two and two together,” one of the lead investigators told Vice.

But a different picture emerges when talking to Russians in Kansas City and Sedalia, the heart of Missouri’s Slavic population. We talked to a half-dozen people, none of whom would agree to be quoted on the record — partly because the story mentions the mafia but also because American caviar is déclassé. If Russians in Missouri are eating spoonbill roe at community gatherings, their hosts might prefer they don’t know.

“We only eat Russian caviar,” said one local Russian. “Imported — from Russia.”

Back on the boat, Hoke and Wells are having a good day.

After just an hour on the water, Hoke has landed his second spoonbill of the day. Once they get the fish aboard the boat, they lasso it by the tail and gills and put it back into the water. These hardy fish continue to thump the side of the boat from time to time. “If you give them a little more line, you’ll see them just swimming along next to the boat,” Wells says.

Wells and Hoke start swapping stories, talking about fishing trips from 50 years ago and spreading the legend of a spoonbiller named Ben, who is 87 years old and deaf as a post but who can outfish anyone on the lake, holding his rod with hands as big as baseball mitts.

It’s a sunny spring Monday, and a handful of other boats are on the water. Guides like Cody Vannattan, from the bait shop, say they get people from all across the country who come out to fish for a few hours and then head home. “I’ve got two guys from Richmond coming tomorrow, driving from Virginia to fish for two hours and then drive home,” he says. “It’s a bucket-list

fish for some guys.”

Most of these folks are now using dipsy divers, which eliminate the need to muscle the pole up and down all day. It’s changing the sport, the men say, and drawing elbow-to-elbow crowds that make the Osage arm “like a zoo” at the beginning and end of the season.

“Weekdays, you used to be the only person out here,” Hoke says. “Since they been running them planer boards, there’s a lot more people doing it. Not everybody wants to come out here and pull this pole all day long. Well, now they can just come out here and, mmmhhhmmm, drink coffee or beer or whatever all day long and wait for a fish to hit.”

The second fish Hoke catches is also male, but it doesn’t really matter to him. He’d just toss out the eggs anyway.

“That $450 fine, that scares me,” he says. “I don’t want no part of that, messing up. If you mess up and don’t do the eggs just right, that’s a $450 fine. There are signs this mindset might be changing. Toward the end of the season, a Lee’s Summit man named Jason Atkins posted a picture of a hulking caviar sandwich to an active Facebook group for Missouri spoonbillers. This pile of butter, bread and caviar was sized like a reuben from Carnegie Deli — where it might retail for $1,000.

Atkins, 40, is an adventurous eater who runs an Instagram account where you can follow his exploits in wild game cooking, including his recent preparation of a wild fox.

Atkins had gone snagging with his family but always thought it was illegal to eat spoonbill eggs. He thinks he might be a forerunner to a new era where Missouri snaggers don’t dump the eggs off the side of the dock.

“I thought it was illegal,” he says. “Somebody corrected me on it and I was like, ‘Well, shoot, I want to try that out,’” Atkins says. “The more guys figure out the actual rules on that, I think there’ll be a few that try it.”

So Atkins made himself a sandwich — toasted white bread with a little butter and a huge heap of black spoonbill caviar, overflowing from the bread and onto the plate. The caviar sandwich is that most decadent and simple of presentations, once a staple of Russian working-class lunches, now such an extravagance that it seems a bit gauche. Except in Missouri.

“I figured, man, I’m gonna load this dude up if it costs that much,” Atkins says. “It was actually pretty excellent. I was pretty stoked to eat it, and I was not let down. It tasted a whole lot better than fox.”