The Kansas City Museum was built in 1910 as a family residence, but it’s been a museum much longer than it was ever a home. It recently reopened after a phased restoration project that has been going on for a decade—longer if you count the newly reopened third floor, which had been off-limits since the 1980s due to fire code violations.

Each room on the entry level of the museum has been painstakingly restored to when the Long family lived there. Wallpaper designs and paint colors were lifted from the architect’s drawings, and family furniture sold off decades ago has been brought back.

“From the very beginning, we said that if we don’t have original material, we won’t try to replicate it or buy something fake that looks old-timey,” says Denise Morrison, the museum’s director of collections. “Instead, we put in materials that are current and modern so that you know what you’re looking at.”

The new Kansas City Museum also blends contemporary art into its space, combining art and history, old and new, house and museum. The second and third floors have a theater and multiple galleries that tell the history of Kansas City through a new lens.

We walked through the new museum with Morrison and curator Lisa Shockley before it opened to the public to uncover the museum’s hidden Easter eggs. Below are five of the museum’s secrets that you wouldn’t notice at first glance.

Eye of the Lion

The museum originally had what Morrison describes as a “huge marble table with big, ancient-looking lions on the side” in the entrance. That table is gone, so the new architectural and design team constructed a sleek, modern front desk with the outline of what the original lions looked like. The new desk won an international award for its design, and the architecture and design team is a local firm that is a woman-led and minority-owned company. Much of the museum’s restoration takes a similar approach, honoring the integrity of the structure as closely as possible in innovative and conscientious ways.

Salamander & Crown

“One feature that people might not notice is the wallpaper in the living room, recreated from the original wallpaper,” Morrison says. The wallpaper’s design features a salamander and crown motif, the royal emblem of Francis I.

“Each room of the home had a particular design theme,” Shockley adds. “The living room was inspired by Francis I.”

The living room and the sun parlor were Mrs. Long’s favorite rooms. The library was Mr. Long’s retreat—it’s Elizabethan-styled with oak-paneled walls and leaded glass bookcases, which are still intact in the museum today.

Coincidental Connection

On the second floor of the museum, an exhibit titled “An Evolving City Landscape” profiles historical figures who helped spur the city’s growth. Black, immigrant, and working-class communities were largely responsible for Kansas City’s industrial growth but are often forgotten.

Lafayette Alonzo Tillman was a business owner, community leader and Kansas City’s second Black police officer. His son, Lon, was a doctor at Wheatley-Provident Hospital. The museum has on display a prescription written by Dr. Lon Tillman during prohibition when liquor was prescribed medicinally to evade the Constitutional ban on alcohol. The museum acquired his prescription serendipitously, Morrison says. “Lisa [Shockley] actually found the prescription while digging through a box at an estate sale.”

Lee’s Leaving

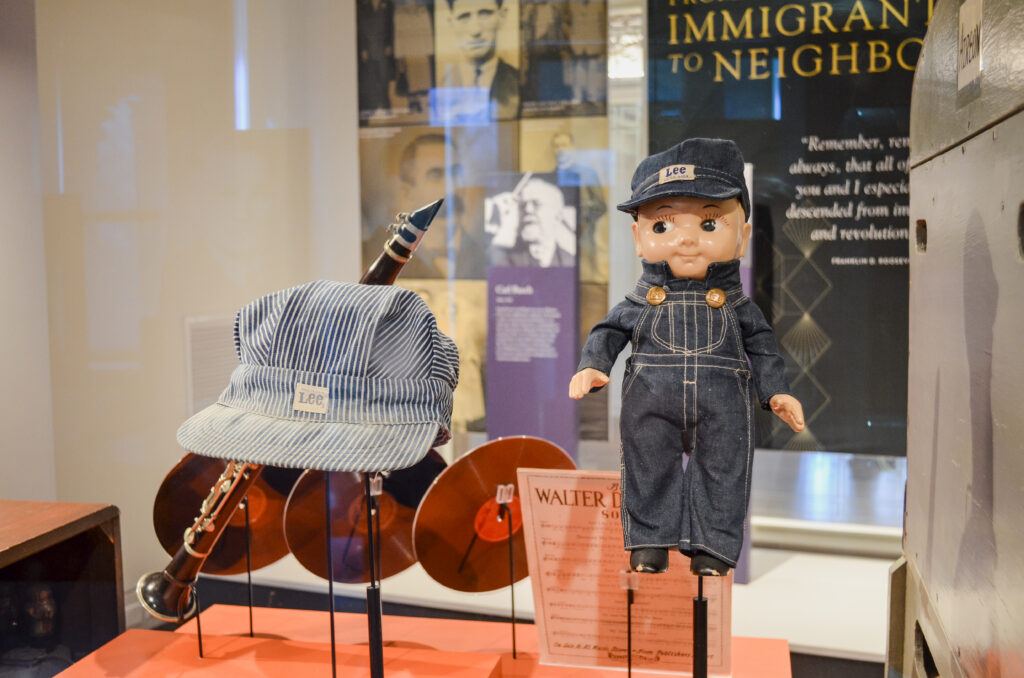

The museum has a variety of items from HD Lee Co., the KC-founded jeans company, which donated artifacts to the museum before moving to North Carolina.

But it’s not jeans that the museum has on display. Lee’s Jeans actually started out as a mail-order food business. Much of the museum’s collection includes early twentieth-century coffee tins and spice containers.

The collection also includes the brand’s signature Buddy Lee doll introduced in the 1920s. “The doll was initially created as a display piece for department stores,” Shockley says. “After becoming popular, it was made into a smaller toy version, which remained in production up until about 1960, and then in the early 80s they brought them back.”

Mirror, Mirror on the Ball

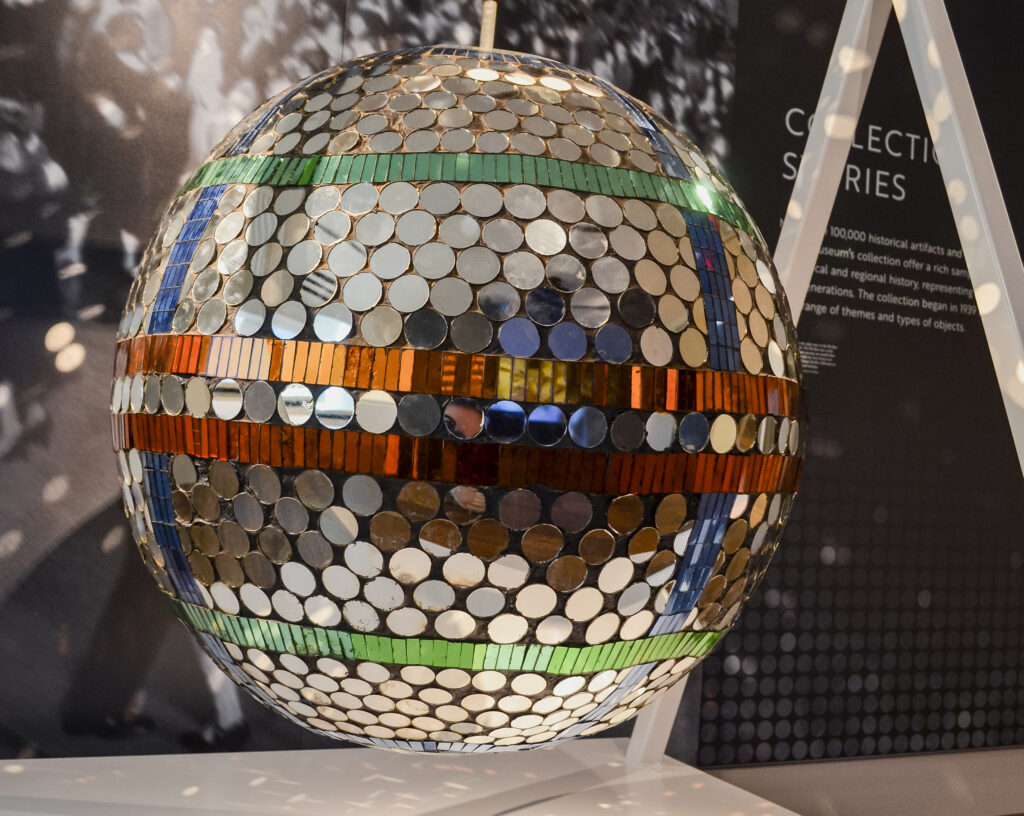

The third floor of the museum has a gallery, “Collection Stories,” that tells the story of El Torreon, a two-story ballroom space on Gillham.

Originally opened in 1927, El Torreon had an upper ballroom for jazz music and a lower ballroom for galas, dinners and other events. And while the exterior of the building at 31st and Gillham hasn’t changed, its interior has taken many forms over the years.

After operating as a ballroom during the jazz era, it closed in 1934 because of the Great Depression. It came back in 1937 and was a roller skating rink and venue for rock ‘n’ roll shows until 1962. Then, in the early ’70s, it became the Cowtown Ballroom, one of the most popular rock venues in the country, hosting artists like Van Morrison, Frank Zappa and Alice Cooper.

The Kansas City Museum has El Torreon’s original two-hundred-pound mirror ball, which has its own storied history. The mirror ball was installed in El Torreon in 1927. But what is not visible on display is the ball’s motor, which has a serial number dating it back to 1918. “It was not uncommon for such things to be purchased as used because they were so expensive,” Shockley says. “It’s likely that it [the mirror ball] had a brief life elsewhere before.”